When I first dove into Anthropic’s multi-agent research system, I noticed something interesting about their 90% speedup. They achieved it through architectural parallelism: multiple subagents exploring different research directions simultaneously. One agent researched semiconductor companies while another investigated supply chains. Simple concept, powerful results.

From what I’ve seen, most tutorials on building multi-agent systems stop at the architecture. They show you the high-level patterns: sequential agents, parallel agents, coordinator patterns. Should your agent work sequentially or in parallel? How should they communicate? What’s the best way to structure the workflow? They draw nice diagrams with boxes and arrows. “Just spawn multiple agents!” they say. But they skip over the crucial implementation question: how do you actually write code that executes agents concurrently without everything breaking?

That’s where concurrency primitives come in. Things like async/await, ThreadPoolExecutor, locks, and semaphores. The low-level tools that make parallel execution work.

Now, if you’re using a high-level framework or an API like AsyncOpenAI that already handles the async part, great! That’s one less thing to implement. Many modern APIs have built-in concurrent execution features.

But here’s why you should still understand these concepts: even with those APIs, you’ll need to add your own concurrency controls. Understanding the primitives lets you modify the wheel for your use case (rather than just reinventing it).

Maybe your framework doesn’t handle backpressure the way you need. Maybe you need to integrate with a custom tool that requires special rate limiting. Maybe you’re debugging why your agents are randomly dropping messages. When you understand the underlying concurrency primitives, you can diagnose issues, customize behavior, and build systems that work reliably at scale.

In this post, you’ll learn how concurrency works in multi-agent systems. We’ll explore how race conditions manifest in LLM systems, implement async/await for massive speedups, build thread-safe state management, and handle backpressure. Most importantly, you’ll understand WHY these patterns exist, so when you encounter concurrency issues in your own systems, you’ll know exactly what’s happening and how to fix it.

The Two Layers of Multi-Agent Concurrency

When you build a multi-agent system, you’re operating at two distinct levels simultaneously.

The first layer is orchestration patterns. This is the architectural view that most tutorials focus on. You might have agents running sequentially where Agent A finishes, passes its output to Agent B, which then passes to Agent C. Or you might run agents in parallel where multiple agents work simultaneously on different aspects of a problem. You could also use a coordinator pattern where a router agent delegates tasks to specialist agents based on the input. Google’s agent design pattern documentation covers these patterns extensively.

The second layer is execution primitives. This is where the rubber meets the road. You need async/await to handle non-blocking LLM API calls. You use ThreadPoolExecutor for I/O-bound parallelism. You implement locks and semaphores to protect shared state. You prevent race conditions that can corrupt your agent’s memory.

Both layers matter because you need architectural plans AND proper wiring to build these systems.

Let me show you what happens when you ignore the second layer.

Race Conditions in Agent State

When you call an LLM API, here’s what happens.

- Your Python code sends the HTTP request (this takes maybe 1 millisecond).

- The request travels over the network to OpenAI’s servers (takes time, but your CPU isn’t doing anything).

- OpenAI’s servers process your request (your CPU is still idle).

- The response travels back over the network (still waiting).

- Your Python code receives and processes the response (maybe another 1 millisecond).

Notice something? You’re waiting around for 90% of the time. Your CPU is just sitting there, doing nothing, while the API does its work.

Now imagine you have three agents that need to run.

- A research agent that gathers information

- An analysis agent that processes findings

- A writer agent that synthesizes everything

If you run them sequentially (one after the other), you’re looking at 15-30 seconds minimum. That adds up fast.

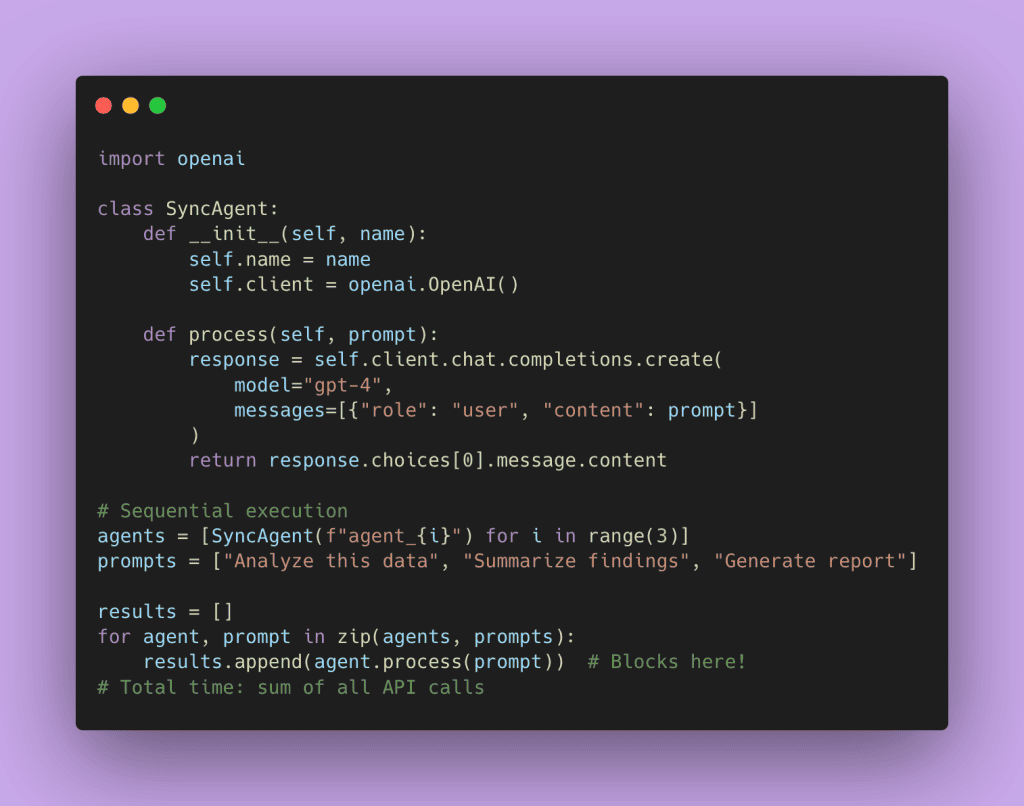

Here’s an example 👇🏾

This works, but it’s slow. Three LLM calls running sequentially means you’re waiting between jobs until the prior agent completes its task(s).

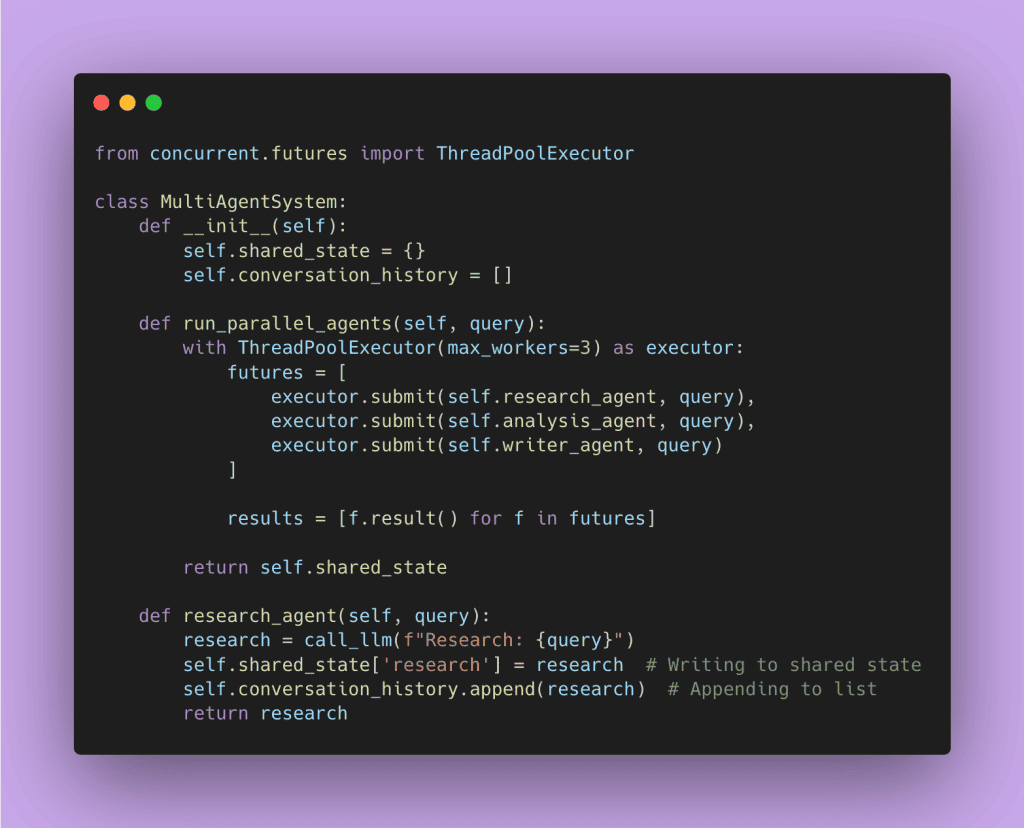

So you think: “I’ll just run them in parallel!” And you try something like this 👇🏾

Now you’ve got a different problem. Multiple agents are writing to shared_state at the same time. They’re all appending to conversation_history simultaneously. And Python lists aren’t thread-safe.

What happens? Sometimes it works fine. Sometimes you get corrupted data. Sometimes entries disappear from your conversation history. This code has critical race conditions that will cause sporadic, hard-to-debug failures in production.

Here’s what could go wrong.

Lost updates: Two agents try to update shared_state

Corrupted conversation history: The conversation_history.append()

Nondeterministic results: Your output depends on thread timing. Run the same inputs twice, get different outputs. This makes debugging feel like trying to catch smoke.

This is exactly the same race condition pattern you see in traditional concurrent programming. The abstraction doesn’t save you from the fundamentals. You’re just dealing with LLMs this time.

If you’re coming from data science and haven’t done much systems programming, let me explain what a race condition is. Imagine two people editing the same document at the same time without any coordination. Person A reads the document, makes changes, and saves. Person B reads the document (before Person A saves), makes different changes, and saves. Whoever saves last overwrites the other person’s work. That’s a race condition.

You’ve probably experienced this when working on the same git branch as a colleague. Having to resolve merge conflicts is like a rite of passage for people who work in tech 😉. If you haven’t experienced it, you will eventually. But merge conflicts are an example of race conditions.

Race conditions are sneaky. When you test your code locally, you run one request at a time. You send a prompt, get a result, check it looks good, and move on. Everything works perfectly every single time.

But once real users start hitting your system, multiple requests arrive simultaneously. User A sends a request to your system. Your system spawns three agents to process it in parallel. All three agents share the same conversation history list. Agent 1 finishes its analysis and tries to append the result. Agent 2 finishes a moment later and tries to append its result. Agent 3 follows right behind doing the same thing.

That’s when things break. Two agents try to append to the list at almost the exact same moment. The list gets corrupted. Messages vanish. You get weird errors that only happen sometimes.

The worst part? This might only fail once every hundred requests, depending on the exact timing. Your tests pass. Your demo works great. Then you deploy, and suddenly you’re getting bug reports about missing conversation history that you can’t reproduce on your laptop.

There are three ways to prevent this nightmare.

- Using Async/Await

- Managing a Thread-Safe State

- Handling Rate Limits to Avoid Backpressure

Async/Await for Speed

LLM API calls are perfect candidates for async programming because they’re I/O-bound. When you make an API call to Claude or GPT-4, you spend maybe 90% of the time just waiting for the network response. Traditional synchronous code blocks the entire thread during that wait. Modern async code uses that waiting time to let other work happen.

You do this as well without realizing it. For humans we call it multi-tasking ✨. An example is cooking dinner. You put water on to boil (that takes about 5-10 minutes), so while it heats up, you chop vegetables or do something else in the meantime. Imagine waiting for the water to come to a boil before cutting your vegetables, it’s so inefficient! Now think of your agents in that manner.

Let me show you what this looks like in practice. Here’s the traditional synchronous approach:

Each call blocks until it completes. If each API call takes 2 seconds, three calls take 6 seconds minimum.

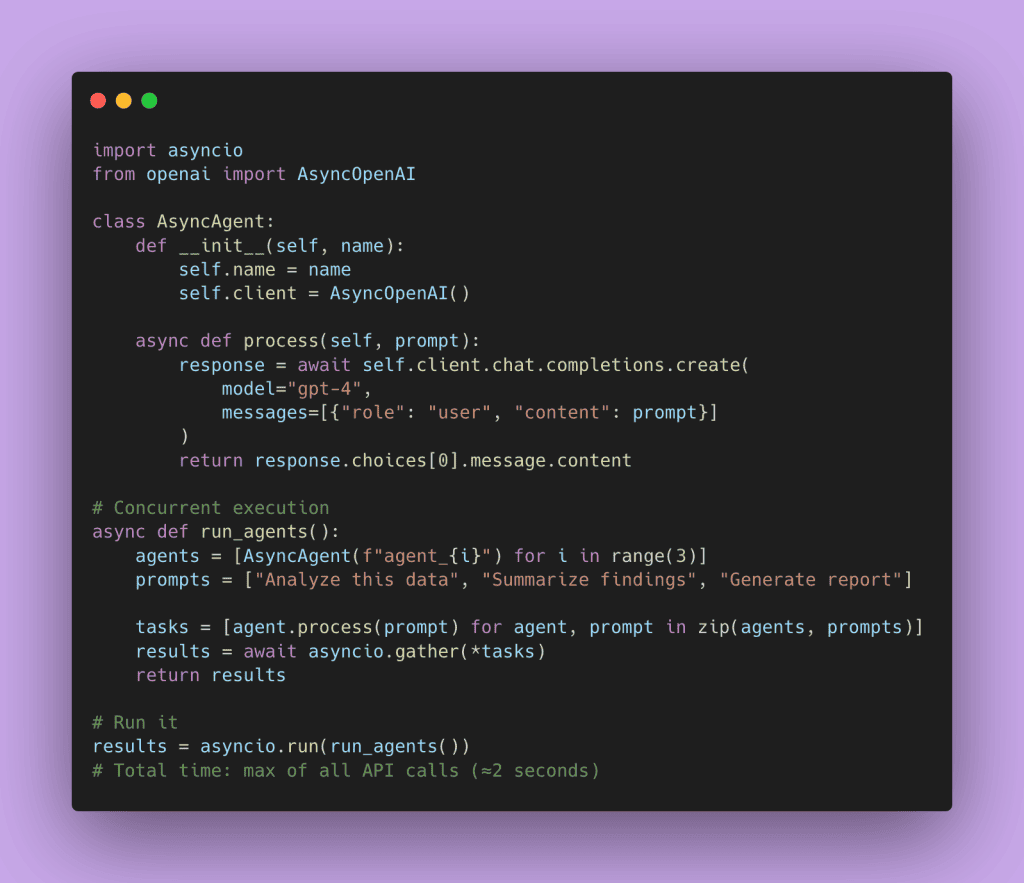

Here’s the async version:

The async version runs all three calls concurrently. Total time is roughly the duration of the slowest call, not the sum of all calls.

For those new to async, here’s a key point: Python’s async isn’t multithreading. It’s cooperative concurrency. When one agent is waiting for an API response, it pauses and lets other agents start their work. The event loop manages who goes next. This keeps everyone busy instead of wasting time waiting. Async isn’t about parallel execution (multiple things happening at once). It’s about not wasting time during waits. While Agent A waits for the network, Agent B can use the CPU to prepare and send its own request.

This works because of Python’s Global Interpreter Lock (GIL). With the GIL, only one thread executes Python code at a time. At first glance, it sounds like a problem. How can async help with concurrency if Python can only do one thing at a time?

There’s an important distinction between CPU-bound work and I/O-bound work.

CPU-bound work means your code is actively computing something. Think of calculating the first million digits of pi or training a neural network. The CPU is constantly busy executing Python instructions. For this kind of work, the GIL is a bottleneck because you genuinely can’t do two computations at once (without using multiprocessing).

I/O-bound work means your code is mostly waiting for something external. Recall from the race condition section when you make an API call to an LLM:

- Your code sends a request (about 0.05 seconds).

- The network does its thing (0.1 seconds).

- The LLM processes your prompt (5-10 seconds).

- The response travels back (0.1 seconds).

- Your code receives it (0.05 seconds).

During this time your Python code is mostly idle.

However, while your code is waiting for that API response (steps 2-4), Python releases the GIL. Other async tasks can run their Python code during that time. When your API response arrives, your code gets the GIL back and continues.

For LLM API calls, you’re spending most of your time waiting on the network, not actively using the CPU. That’s why async gives you massive speedups despite the GIL.

requests library in an async function. It blocks the entire event loop, defeating the purpose. You must use async-compatible libraries like aiohttp or AsyncOpenAI.

Thread-Safe State Management

Agents need to communicate and share context. But sharing mutable state between concurrent agents is where race conditions breed. You have two fundamental approaches: make your state immutable (this comes from functional programming, where you never modify data, you create new copies), or use explicit locking (this is the traditional imperative programming approach, where you protect data so only one thing can modify it at a time).

Most data scientists primarily work in Python, which is an imperative language. You write instructions like “do this, then do that, then update this variable.” Functional programming languages like Scala, Haskell, or Clojure take a different approach. They avoid changing state entirely. Instead of modifying a list, you create a new list with your changes. It sounds inefficient, but it eliminates entire classes of bugs, especially in concurrent systems.

For multi-agent systems, both approaches work. The functional approach (immutability) is often cleaner and safer. The imperative approach (locks) gives you more control when you absolutely need shared mutable state.

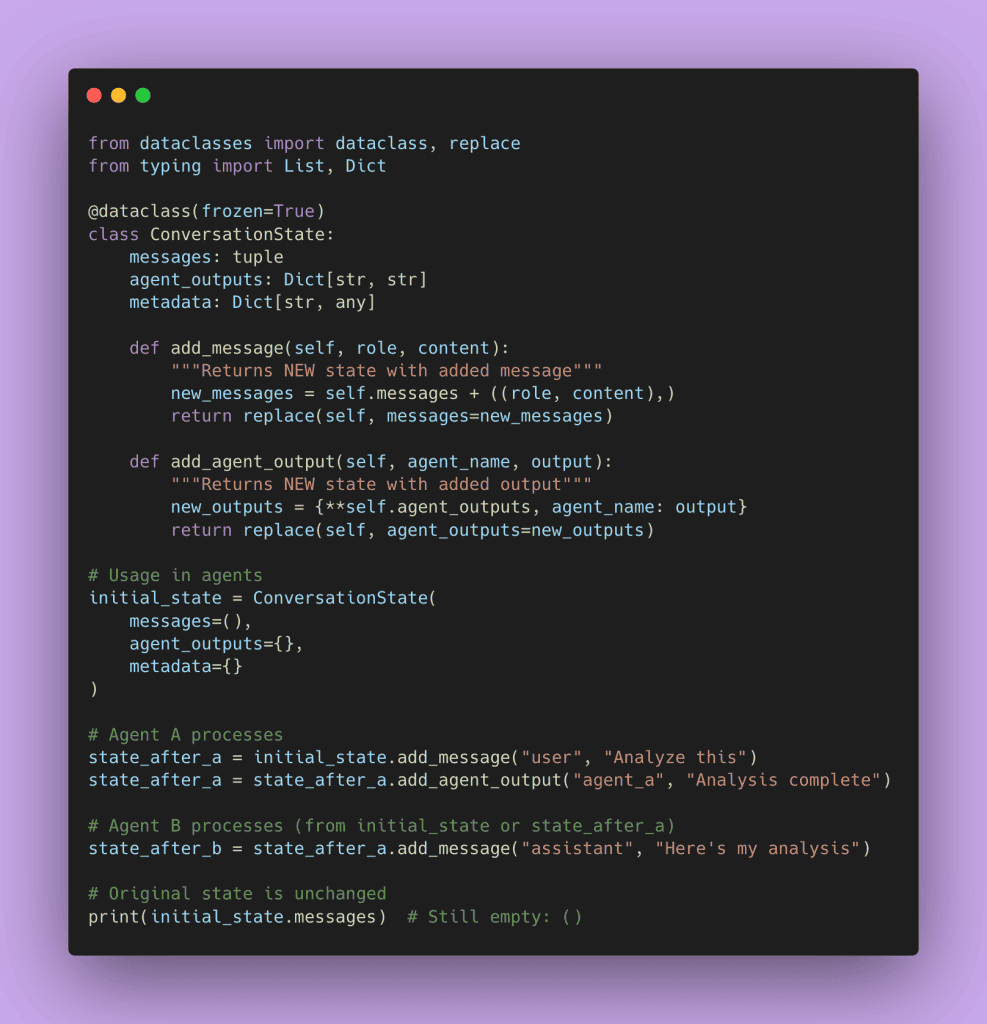

The immutable state approach means each state update creates a new state rather than modifying existing state. Here’s how it works.

Each method returns a new state object. The old state remains unchanged. This eliminates race conditions because there’s no shared mutable state to conflict over.

Use immutable state when your workflow is sequential or has a clear data flow. It’s perfect for pipelines where Agent A feeds Agent B feeds Agent C, and each state builds on the previous output.

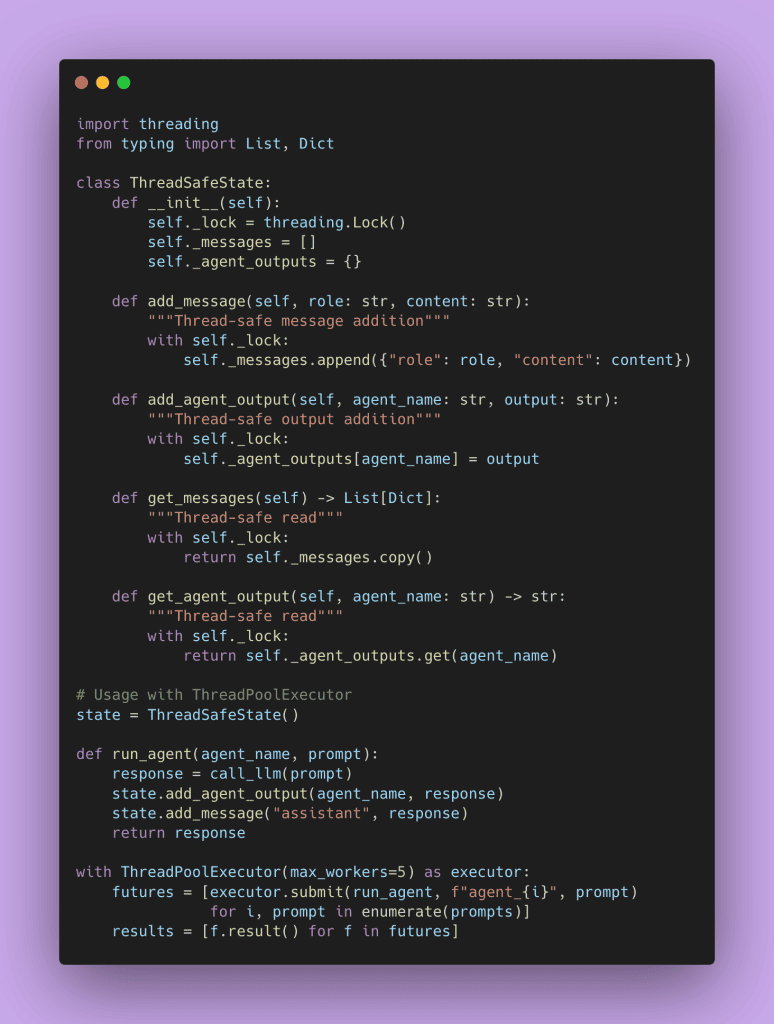

But sometimes you truly need shared mutable state. You need explicit locking when multiple agents are writing to a shared context simultaneously.

The lock ensures only one thread modifies the state at a time. Other threads wait their turn. This is classic concurrency control, but applied to agent state.

Which approach should you use? Start with immutable state if possible. It’s simpler to reason about and less error-prone. Add locks only when you truly need multiple concurrent writers. For sequential workflows or workflows with a single writer and multiple readers, immutable state is cleaner.

Here’s a serious pitfall to watch out for: lists aren’t thread-safe in Python (this was mentioned earlier). Even simple operations like self.conversation.append(message) can corrupt your list if multiple threads execute it concurrently. Python’s list.append() isn’t atomic despite looking like a single operation. Under the hood, it involves multiple steps: reading the current length, allocating space, writing the new element, updating the length. If two threads interleave those steps, you get corruption.

The solution? Use queue.Queue for thread-safe appending, or use locks around list operations. I’ve spent hours debugging intermittent list corruption before I learned this lesson.

Rate Limiting and Backpressure

Production systems hit API rate limits. OpenAI, Anthropic, and other providers limit how many requests you can make per minute. If you naively run 100 agents in parallel, you’ll burn through your quota in seconds, get 429 errors, and waste money on failed requests.

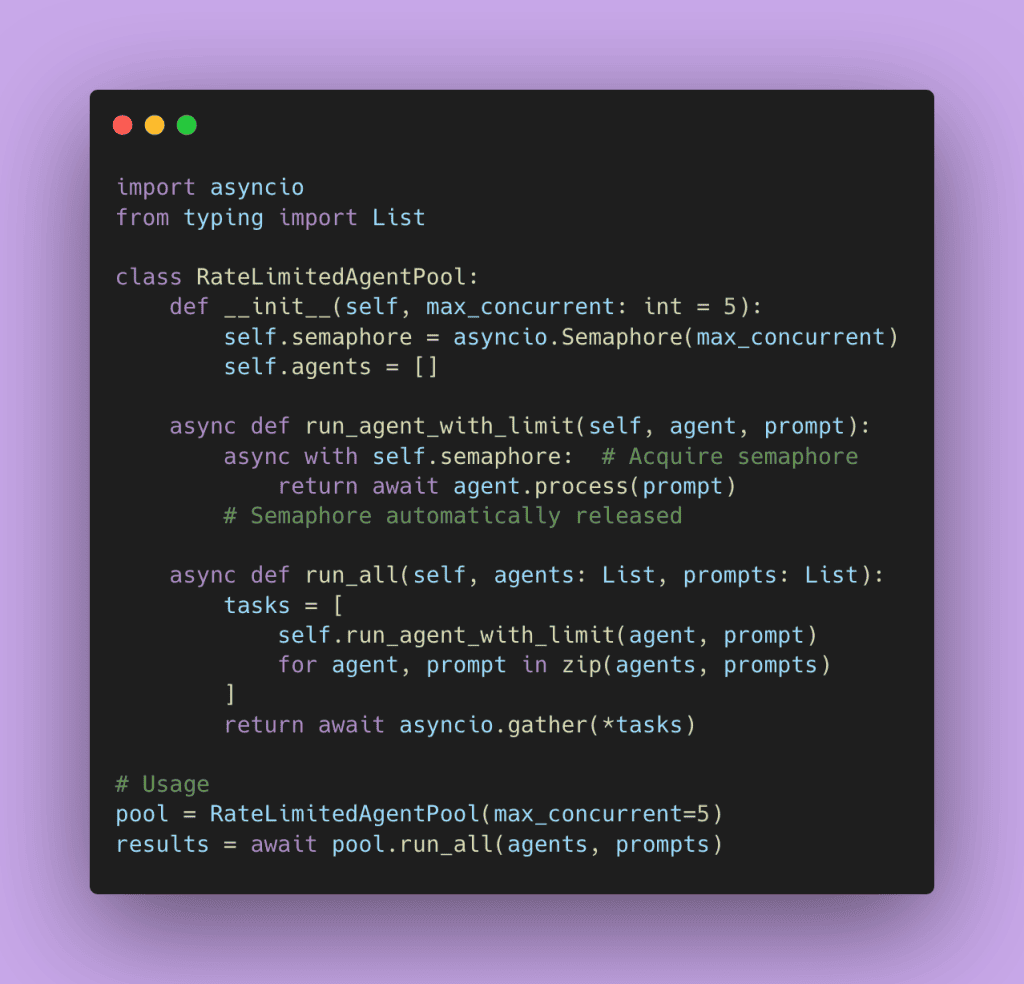

You need a way to control concurrency, and semaphores solve this problem. A semaphore limits how many operations can run concurrently.

Here’s how it works. Imagine you’re at a coffee shop with 5 baristas working. Even if 50 people walk in wanting coffee, only 5 orders get made simultaneously. Customer 6 through 50 wait in line. As soon as a barista finishes an order and becomes available, the next customer in line gets served. The coffee shop is always working at maximum capacity without overwhelming the staff.

That’s exactly what a semaphore does for your multi-agent system. You set max_concurrent=5, and even if you have 100 agents ready to call the LLM API, only 5 run at a time. As each agent finishes, the next one in line starts. This keeps your system running efficiently while respecting API rate limits and not burning through your budget.

You also need to handle backpressure. Backpressure is what happens when work arrives faster than your system can process it. Imagine you have 100 agents ready to run, but your API can only handle 5 requests per second due to rate limits. Those 95 waiting agents create pressure on your system. Or maybe one agent takes 30 seconds instead of the usual 2 seconds. Now everything behind it is backed up waiting.

I ran into a similar issue with a computer vision model deployed on AWS SageMaker. The endpoint received image tiles from large NTIF files, but I only had one instance running (ml.g4dn.xlarge). Tiles arrived faster than the single instance could process them. The task queue depth hit 96, meaning 96 tiles were waiting in line. The endpoint hit its connection limit and started rejecting new requests. The entire system ground to a halt.

The question is: what does your system do with that pressure? Does it crash? Does it queue everything up until you run out of memory? Does it drop requests? My system did all of the above before I fixed the problem. Your system should degrade gracefully instead of cascading into failure.

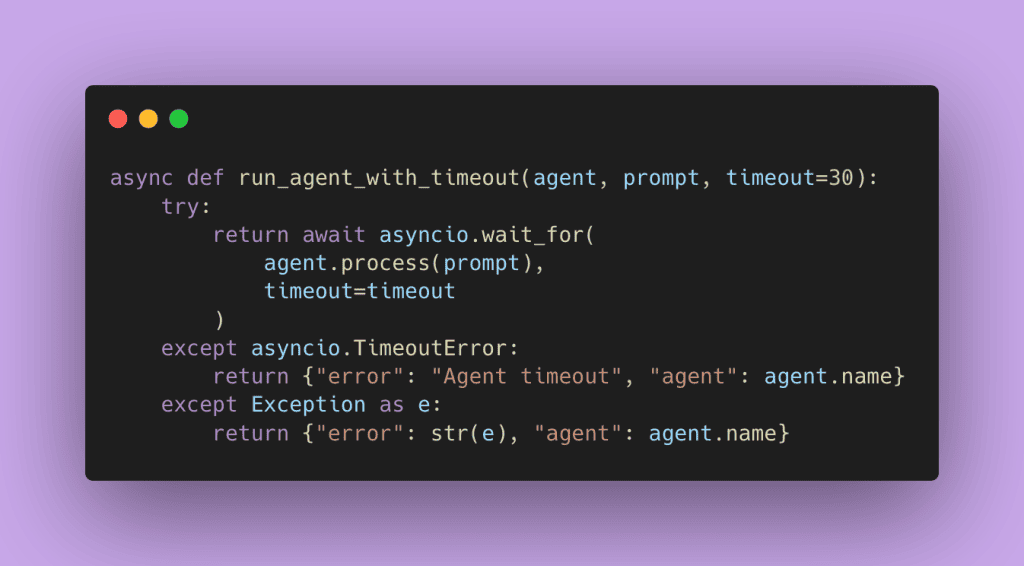

Here’s how you handle it. Set timeouts so slow agents don’t block forever. Handle partial results so if Agent 2 times out, you can still use the results from Agents 1 and 3. Decide whether to retry failed agents or skip them and move on. Monitor your queue depth so you know when backpressure is building up.

The tradeoff here is performance versus cost. More parallelism means faster results but higher API costs. I usually start with max_concurrent=5 and tune based on actual API limits and budget. Monitor your rate limit usage and adjust accordingly.

Putting It All Together: The Production Architecture

Now let’s combine everything into launch-ready code. This example uses three layers: clean architecture with interface, concurrency primitives for correct execution, and orchestration patterns for workflow control.

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

from dataclasses import dataclass, replace

import asyncio

from typing import List, Dict, Optional

from openai import AsyncOpenAI

# Layer 1: Clean Architecture - Interfaces

class Agent(ABC):

@abstractmethod

async def process(self, prompt: str, context: "ConversationState") -> str:

pass

@dataclass(frozen=True)

class ConversationState:

"""Immutable state object"""

messages: tuple

agent_outputs: Dict[str, str]

def add_message(self, role: str, content: str):

new_messages = self.messages + ((role, content),)

return replace(self, messages=new_messages)

def add_output(self, agent_name: str, output: str):

new_outputs = {**self.agent_outputs, agent_name: output}

return replace(self, agent_outputs=new_outputs)

# Layer 2: Concrete Agent Implementation

class ResearchAgent(Agent):

def __init__(self, name: str):

self.name = name

self.client = AsyncOpenAI()

async def process(self, prompt: str, context: ConversationState) -> str:

messages = [{"role": role, "content": content}

for role, content in context.messages]

messages.append({"role": "user", "content": prompt})

response = await self.client.chat.completions.create(

model="gpt-4",

messages=messages

)

return response.choices[0].message.content

# Layer 3: Orchestration with Concurrency Control

class ParallelOrchestrator:

def __init__(self, max_concurrent: int = 5):

self.semaphore = asyncio.Semaphore(max_concurrent)

async def run_with_limit(self, agent: Agent, prompt: str,

state: ConversationState, timeout: int = 30):

async with self.semaphore:

try:

result = await asyncio.wait_for(

agent.process(prompt, state),

timeout=timeout

)

return {"agent": agent.name, "result": result, "error": None}

except asyncio.TimeoutError:

return {"agent": agent.name, "result": None, "error": "timeout"}

except Exception as e:

return {"agent": agent.name, "result": None, "error": str(e)}

async def run_parallel(self, agents: List[Agent], prompts: List[str],

initial_state: ConversationState):

tasks = [

self.run_with_limit(agent, prompt, initial_state)

for agent, prompt in zip(agents, prompts)

]

results = await asyncio.gather(*tasks, return_exceptions=True)

# Build new state from results

new_state = initial_state

for result in results:

if isinstance(result, dict) and result.get("result"):

new_state = new_state.add_output(

result["agent"],

result["result"]

)

return new_state, results

class SequentialOrchestrator:

async def run_sequential(self, agents: List[Agent], prompts: List[str],

initial_state: ConversationState):

state = initial_state

results = []

for agent, prompt in zip(agents, prompts):

try:

result = await agent.process(prompt, state)

state = state.add_output(agent.name, result)

state = state.add_message("assistant", result)

results.append({"agent": agent.name, "result": result, "error": None})

except Exception as e:

results.append({"agent": agent.name, "result": None, "error": str(e)})

return state, results

# Usage

async def main():

# Create agents

agents = [

ResearchAgent("researcher_1"),

ResearchAgent("researcher_2"),

ResearchAgent("researcher_3")

]

prompts = [

"What are the latest AI trends?",

"Summarize recent LLM research",

"Identify key challenges in multi-agent systems"

]

initial_state = ConversationState(messages=(), agent_outputs={})

# Parallel execution with rate limiting

orchestrator = ParallelOrchestrator(max_concurrent=3)

final_state, results = await orchestrator.run_parallel(

agents, prompts, initial_state

)

for result in results:

print(f"{result['agent']}: {result['result'][:100]}...")

asyncio.run(main())This architecture follows the Interface Segregation Principle and Dependency Inversion from Clean Architecture. Your Agent interface defines what agents do, not how. The orchestrators handle concurrency without agents needing to know. You can swap between parallel and sequential execution by changing the orchestrator.

The immutable ConversationState prevents race conditions. The semaphore controls concurrency. The timeout handling prevents cascading failures.

Handling Errors in Parallel Execution

One critical aspect of production systems is error handling. In parallel execution, one agent failure shouldn’t kill everything. Notice in the ParallelOrchestrator above how we use return_exceptions=True in asyncio.gather(). This ensures all tasks complete even if some fail.

Here’s why this matters. By default, asyncio.gather() raises an exception if any task fails, stopping all other tasks. That’s rarely what you want in a multi-agent system. If Agent 2 times out, you still want results from Agents 1 and 3.

The code handles three types of failures:

- Timeouts: When an agent takes too long,

asyncio.wait_for()raisesTimeoutError. We catch it and return an error dict instead of crashing. - API errors: When the LLM API returns an error (rate limit, invalid request, etc.), we catch the exception and return it as part of the results.

- Partial results: The orchestrator processes all results, including errors, and builds state from successful completions only.

This is production-ready code that handles the real-world messiness of concurrent agent execution.

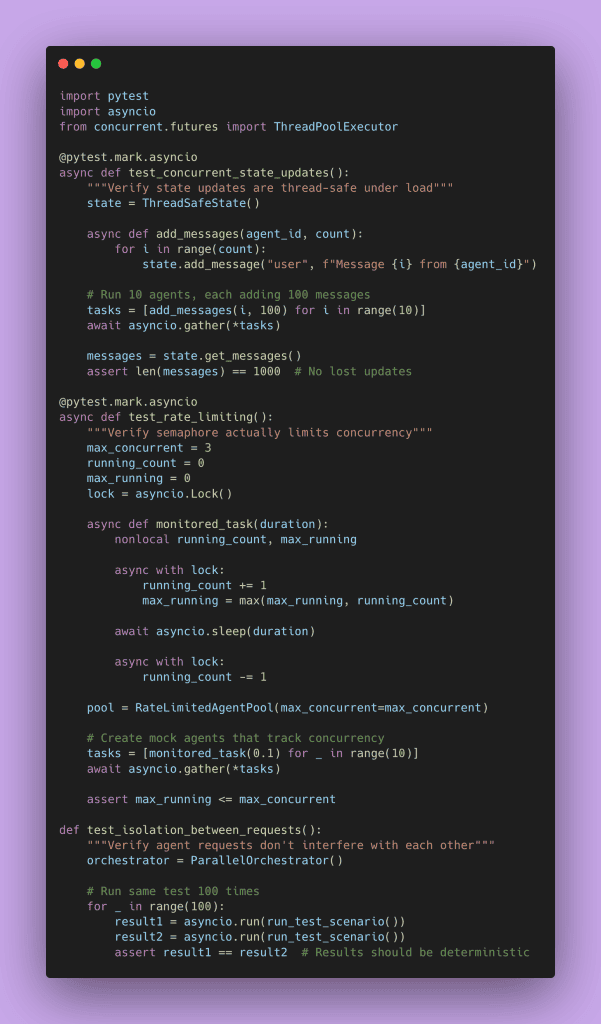

Testing Concurrent Agents

Normal unit tests aren’t sufficient for concurrent code. Race conditions only appear under specific timing conditions. You need tests that create those conditions deliberately.

Here’s an example testing strategy.

Load testing is also critical. Use tools like locust or pytest-xdist to simulate multiple concurrent users hitting your multi-agent system. Watch for memory leaks, increasing response times, or sporadic failures under load.

The Bottom Line

Building production multi-agent systems requires understanding both layers of concurrency.

You need high-level architectural patterns to organize your agents. Sequential workflows, parallel execution, coordinator patterns. These define what your system does.

You also need low-level concurrency primitives to execute correctly. Async/await for speed, locks for safety, semaphores for rate limiting. These define how your system does it.

Key Takeaways

Async/await isn’t optional. LLM API calls are I/O-bound, and parallel execution can cut your processing time by 90%. Use asyncio.gather() for parallel agents, and always use async-compatible libraries.

Race conditions are silent killers waiting to destroy your multi-agent systems. Protect shared state with either immutability or locks. Never assume operations are thread-safe unless you’ve verified it.

Rate limiting prevents disasters. Use semaphores to control concurrency and stay within API limits. Handle timeouts and errors gracefully.

Testing requires special attention. Race conditions don’t show up in normal unit tests. You need hammer tests, load tests, and concurrency-specific assertions.

The machine learning engineers who succeed in building multi-agent systems understand both layers. You can’t separate the architecture from the implementation. Those elegant pattern diagrams need robust concurrent execution underneath, or they’ll fail in production.

Start by picking one multi-agent pattern. Implement it using the concurrency primitives from this post. Test it thoroughly under load. Then expand to more complex workflows. That’s how you build multi-agent systems that are robust.

What patterns are you using in your multi-agent systems? Have you encountered race conditions in production?

Thanks for reading and happy coding 👍🏾.