Silent data corruption is the worst kind of bug. No errors thrown. No warnings logged. Just wrong data that you’ll spend hours tracking down.

This happens with protobuf schema mismatches. Maybe your client uses v2 where field 47 means “user_id”, but your server expects v3 where field 47 means “session_token”. The code runs fine. The communication succeeds. But you’re corrupting data without realizing it.

Tokenizers cause the exact same problem. Same mechanics, different domain. A model trains with one vocabulary where token 5234 means “algorithm”. You load it later and use a different tokenizer where token 5234 means “method”. The model receives syntactically valid input but semantically wrong data. Performance tanks. No error appears.

I’ve spent almost a week on this exact bug. A fine-tuned model suddenly started generating nonsense. The loss curves looked great. Validation metrics were solid. But in production, it was generating pure garbage. The model was trained with one vocabulary, but inference was using a completely different one. Same token IDs, different meanings.

If you’ve worked with Protocol Buffers (protobuf for short) or JSON serializers, you already understand 80% of what tokenizers do.

Both tokenizers and serializers use integer IDs as mappings. Both require strict version control. Both fail silently when mismatched. The difference is protobuf converts objects to bytes while tokenizers convert text to integers.

Who This Is For

This article assumes you’ve worked with machine learning models before. You don’t need to be an expert, but you should be comfortable with:

- Loading and using pre-trained models (HuggingFace, OpenAI API, etc.)

- Basic Python data structures (lists, dictionaries)

- Running Python code and reading error messages

- The concept that models train on data and make predictions

If you’ve fine-tuned a model, debugged API calls, or built an LLM-powered application, you’re good to go.

Protobuf knowledge helps but isn’t required. I’ll explain the relevant parts as we go.

If You Know Protobuf, You Know Tokenizers

Protobuf uses field IDs instead of field names.

message User {

int32 id = 1;

string name = 2;

string email = 3;

}Those numbers are permanent. Once assigned, you can’t reuse them. This prevents the nightmare scenario where old services think field 4 means “age” but new services think it means “score”.

Imagine this scenario: someone deprecates field 7 (maybe it was “timestamp”). Three months later, a different developer adds a new field and reuses field ID 7 for “description” (a string). Old services still running expect field 7 to be an integer timestamp. New services send a string. The communication succeeds syntactically BUT FAILS semantically. User sessions might terminate unexpectedly. Analytics might show impossible values. No error messages. Just silent corruption.

The debugging process would be painful because everything looks normal. Recent deployments check out. Data at the source is clean. Error logs are empty. Someone would need to manually inspect serialized messages to notice the type mismatch.

Protobuf enforces strict rules about field IDs for exactly this reason. Once assigned, they’re permanent. You can deprecate fields, but you can’t reuse their IDs.

Tokenizers follow identical rules. The vocabulary is your schema, while token IDs are field IDs. Change that vocabulary without updating the model and you break the semantic mapping. The model thinks token 5234 means one thing while your new tokenizer uses it for something else

Why Not Just Use Characters or Words?

Neural networks need numbers, not text. Specifically, they need sequences of numbers. When you tokenize “hello”, you get a list of integers like [104, 101, 108, 108, 111]. The model processes this array of numbers, not the original text.

The question is: how do you convert text to numbers efficiently?

Character-level tokenization is one approach. Map each character to an ID (a=1, b=2, etc.). But this is inefficient because the word “hello” takes 5 tokens – one for each letter.

Word-level tokenization seems better. Map each word to an ID (the=1, cat=2, sat=3). But English has hundreds of thousands of words. Your vocabulary would explode in size. Worse, new words break the system completely.

Byte Pair Encoding (BPE) solved this with a clever compromise.

Start with characters, then iteratively merge the most frequent pairs. If “th” appears constantly in your training data, merge it into one token. If “the” appears constantly, merge “th” and “e” into “the”. This way, common words become single tokens while rare words split into subwords. You never encounter unknown text because you can fall back to character-level tokens.

The genius of BPE is adaptive compression. “electroencephalography” becomes [“electro”, “encephal”, “ography”] instead of 22 character tokens or one unknown word token.

But there’s a crucial detail: merge order creates dependencies. If you merge “th” early in training, then “the” can be created by merging “th” + “e”. But if “he” was merged first, you can’t create “the” as a single token because “h” and “e” are no longer adjacent. They’re already part of “he”. This means the order you learn merges directly impacts your final vocabulary. Two tokenizers trained on similar data can end up with different vocabularies just because of minor differences in merge order.

This is why you can’t mix and match tokenizers between models. They’re not just different schemas; they’re different compression histories.

Building BPE From Scratch

The best way to understand BPE is to build one. We’ll start simple and add complexity as we go.

First, a character-level tokenizer. This is the baseline we’re trying to improve.

class CharacterTokenizer:

def __init__(self):

self.char_to_id = {chr(i): i for i in range(256)}

self.id_to_char = {i: chr(i) for i in range(256)}

def encode(self, text):

return [self.char_to_id[char] for char in text]

def decode(self, tokens):

return ''.join([self.id_to_char[token] for token in tokens])

tokenizer = CharacterTokenizer()

tokens = tokenizer.encode("hello")

print(f"'hello' -> {tokens}")

# Output: 'hello' -> [104, 101, 108, 108, 111]This works, but it’s inefficient. We’re using five tokens for a simple word like “hello”.

BPE improves on this by learning which character pairs appear frequently and merging them. The implementation looks more complex, but the logic is straightforward: count pairs, merge the most frequent one, repeat.

from collections import Counter

class BPETokenizer:

def __init__(self, vocab_size=500):

self.vocab_size = vocab_size

self.merges = {}

self.vocab = {chr(i): i for i in range(256)}

def get_pairs(self, tokens):

pairs = []

for i in range(len(tokens) - 1):

pairs.append((tokens[i], tokens[i + 1]))

return pairs

def train(self, texts):

corpus = [list(text) for text in texts]

while len(self.vocab) < self.vocab_size:

pair_counts = Counter()

for tokens in corpus:

pairs = self.get_pairs(tokens)

pair_counts.update(pairs)

if not pair_counts:

break

best_pair = pair_counts.most_common(1)[0][0]

new_token = ''.join(best_pair)

new_id = len(self.vocab)

self.vocab[new_token] = new_id

self.merges[best_pair] = new_token

new_corpus = []

for tokens in corpus:

i = 0

new_tokens = []

while i < len(tokens):

if i < len(tokens) - 1 and (tokens[i], tokens[i + 1]) == best_pair:

new_tokens.append(new_token)

i += 2

else:

new_tokens.append(tokens[i])

i += 1

new_corpus.append(new_tokens)

corpus = new_corpus

def encode(self, text):

tokens = list(text)

while len(tokens) > 1:

pairs = self.get_pairs(tokens)

valid_pairs = [(i, pair) for i, pair in enumerate(pairs)

if pair in self.merges]

if not valid_pairs:

break

i, pair = valid_pairs[0]

new_token = self.merges[pair]

tokens = tokens[:i] + [new_token] + tokens[i+2:]

return [self.vocab[token] for token in tokens]

def decode(self, token_ids):

id_to_token = {v: k for k, v in self.vocab.items()}

tokens = [id_to_token[tid] for tid in token_ids]

return ''.join(tokens)Now let’s see this in action with a small training set. I’m using comparative adjectives because they have obvious patterns (low/lower/lowest all share “low”):

texts = [

"low lower lowest",

"low lower lowest",

"new newer newest",

"wide wider widest"

]

tokenizer = BPETokenizer(vocab_size=300)

tokenizer.train(texts)

tokens = tokenizer.encode("lowest")

print(f"'lowest' -> {tokens}")

# Might output: 'lowest' -> [263, 268]

# Where 263 = "low" and 268 = "est"Watch what happened. The tokenizer learned that “low”, “er”, and “est” appear frequently across our training data. It merged them into single tokens during training. Now when we encode “lowest” it recognizes the patterns and uses just 2 tokens instead of 6 character-level tokens. That’s the efficiency gain from BPE.

Version Mismatches in Production

Picture this scenario: you fine-tune a model and save the weights. Everything looks good. Weeks later, you load the model for deployment and grab the base tokenizer by default because it’s what’s available.

The problem? Your fine-tuned model learned associations with one vocabulary. Token 5234 meant “algorithm” during training. But the base tokenizer uses token 5234 for “method”. Same ID, completely different meaning.

Because token IDs are just integers. Python sees [42, 123, 5234] as a perfectly valid list. The model receives syntactically correct input. Although, it’s semantically wrong. There are no error messages, just degraded performance that you’ll spend days debugging.

This is the same silent failure we saw with protobuf field IDs. The code runs. The data flow. But the semantic mapping is broken.

The fix is straightforward once you understand the problem. Never save model weights without their tokenizer.

from transformers import AutoTokenizer, AutoModel

def save_model_checkpoint(model, tokenizer, path):

"""Never save one without the other."""

model.save_pretrained(f"{path}/model")

tokenizer.save_pretrained(f"{path}/tokenizer")

def load_model_checkpoint(path):

"""Always load together."""

model = AutoModel.from_pretrained(f"{path}/model")

tokenizer = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained(f"{path}/tokenizer")

return model, tokenizerModel weights and tokenizers are version-locked dependencies. You wouldn’t deploy code that depends on library v2 while your production environment runs v1. Same principle applies here. Treat them as a coupled pair, not separate artifacts.

Context Windows Are Smaller Than You Think

When you see “8k context window” in model specs, that number means the model can process 8k tokens total. Not 8,000 characters. Not 8,000 words. Tokens.

This creates overhead you might not expect. System prompts consume tokens before your actual input even starts. That innocent-sounding instruction “You are a helpful assistant” costs you about 6 tokens on every single API call. It’s like paying a transaction fee each time.

Domain-specific text makes this worse. Medical reports burn through tokens fast. Specialized terminology like ‘encephalopathy‘ or ‘myocardial infarction‘ gets segmented into multiple tokens, while everyday equivalents like ‘brain disease‘ or ‘heart attack‘ might be just one or two tokens each. Same information, completely different token cost.

Consider what happens with a contract review system processing 50-page contracts. If your token budget runs out by page 15, the context window stops accepting more text. No error message. No warning. The system keeps running, but it’s only seen the first 15 pages. Any critical clauses in the remaining 35 pages? Completely missed. This kind of silent failure is dangerous in production systems because everything appears to work fine on the surface.

You need to calculate your actual usable budget.

from transformers import AutoTokenizer, AutoModel

def calculate_usable_tokens(model_max_tokens, system_prompt,

expected_response_length):

tokenizer = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained("your-model-name") # replace this

system_tokens = len(tokenizer.encode(system_prompt))

buffer = int(expected_response_length * 1.1)

usable = model_max_tokens - system_tokens - buffer

return {

"total": model_max_tokens,

"system_prompt": system_tokens,

"response_buffer": buffer,

"usable_for_input": usable,

"utilization": usable / model_max_tokens

}

budget = calculate_usable_tokens(

model_max_tokens=8192,

system_prompt="You are a contract review assistant. Analyze for risks.",

expected_response_length=500

)

print(f"Usable tokens: {budget['usable_for_input']}")

print(f"Utilization: {budget['utilization']:.1%}")This function does the math for you. It accounts for your system prompt overhead, reserves space for the response, and adds a 10% buffer for safety. That buffer matters because token boundaries can be unpredictable, especially with special characters or formatting.

HF_TOKEN in your environment before downloading models from HuggingFace.

Special tokens add another layer of invisible overhead. Tokens like <|endoftext|>, <|padding|>, and <|sep|> don’t appear in your raw text, but they count toward your limit. Budget at least 10-20 tokens per request for these hidden costs. Otherwise you’ll be confused when your carefully calculated token counts don’t match reality.

The Token Tax

GPT’s tokenizer was trained primarily on English internet text. This creates problems when you feed it specialized vocabulary from domains like medicine, law, or programming. The tokenizer hasn’t seen these terms frequently during training, so it doesn’t know how to encode them efficiently.

Watch what happens with medical terminology:

from transformers import AutoTokenizer

tokenizer = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained("gpt2")

normal_text = "The patient has a headache"

medical_text = "The patient has encephalopathy"

normal_tokens = tokenizer.encode(normal_text)

medical_tokens = tokenizer.encode(medical_text)

print(f"Normal: {len(normal_tokens)} tokens")

print(f"Medical: {len(medical_tokens)} tokens")

print(f"\nMedical tokens: {tokenizer.convert_ids_to_tokens(medical_tokens)}")

# Output:

# Normal: 6 tokens

# Medical: 8 tokens

# Medical tokens: ['The', 'Ġpatient', 'Ġhas', 'Ġencephal', 'opathy']“Headache” gets encoded as a single token because it’s common everyday vocabulary. But “encephalopathy” gets split into subwords because the tokenizer rarely saw this medical term during training. This inefficiency compounds across an entire document. A medical report can use 2-3x more tokens than similar content using everyday vocabulary, even though they’re conveying the same information.

The consequences go beyond just burning through your token budget faster. When you split “encephalopathy” into [“encephal”, “opathy”], you’re fragmenting the concept across multiple tokens. The model has to reconstruct the semantic meaning from these pieces instead of recognizing it as a single unit. This can degrade performance on domain-specific tasks.

Code has the same problem, but worse.

code_text = "def fibonacci(n): return n if n <= 1 else fibonacci(n-1) + fibonacci(n-2)"

prose_text = "The function calculates Fibonacci numbers using recursion with base cases."

code_tokens = tokenizer.encode(code_text)

prose_tokens = tokenizer.encode(prose_text)

print(f"Code: {len(code_tokens)} tokens")

print(f"Prose: {len(prose_tokens)} tokens")

print(f"Ratio: {len(code_tokens) / len(prose_tokens):.2f}x")

# Output:

# Code: 24 tokens

# Prose: 13 tokens

# Ratio: 1.85xThe code snippet uses nearly twice as many tokens as the prose explanation. Function names like calculate_weighted_average_excluding_outliers get split into 8+ tokens each. Brackets, parentheses, and operators all become separate tokens. If you’re building systems that send code to LLMs, you’re paying a significant token tax compared to natural language.

For domain-specific systems, this inefficiency adds up quickly.

Custom tokenizers trained on your domain’s text can reduce token usage by 30-40% for specialized content like legal contracts or medical reports. That’s the difference between fitting a full 50-page document in your context window or only getting through 15 pages before hitting the limit.

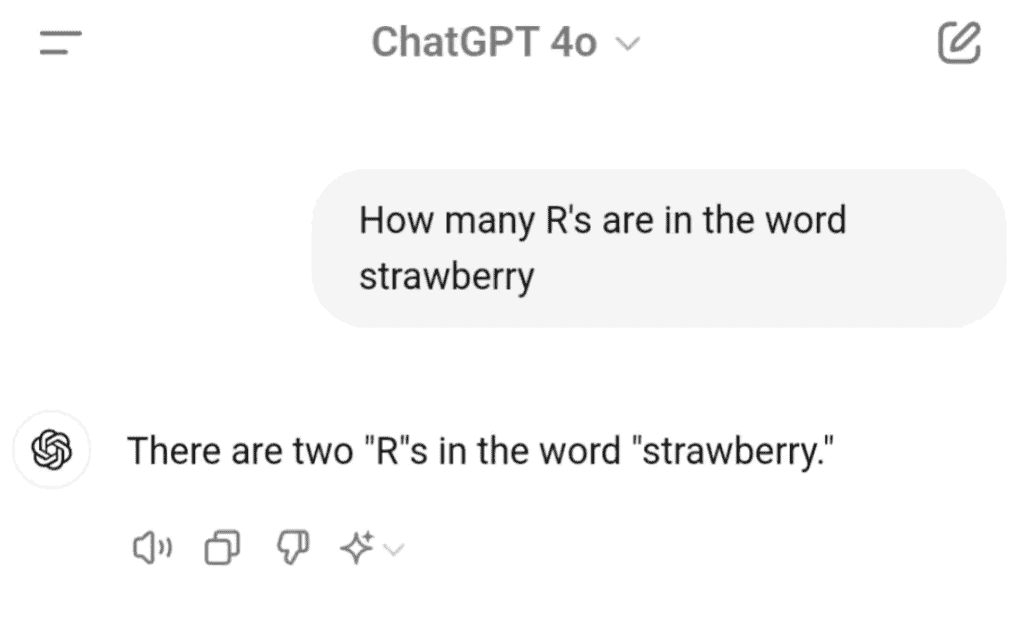

The Strawberry Problem

Back in 2024, ChatGPT went viral because it didn’t know how many r’s are in the word strawberry.

I’m going to defend ChatGPT here.

The model never sees “strawberry” as a sequence of individual characters. It sees tokens, probably something like ["straw", "berry"]. To count the r’s accurately, it would need to know that “straw” contains one r and “berry” contains two. But it doesn’t have that information because it’s working with compressed token representations, not raw characters.

And it’s not just ChatGPT. Most LLMs at that time fail this question for the same reason. They’ll confidently say 2 when the correct answer is 3.

This limitation affects more than just counting exercises. Models struggle with character-level tasks across the board: spelling corrections, palindrome detection, exact string matching, and any task that requires reasoning about individual letters rather than semantic meaning.

When your model behaves unexpectedly on these kinds of tasks, check the tokenization:

def debug_tokenization(text, tokenizer):

tokens = tokenizer.encode(text)

token_strs = tokenizer.convert_ids_to_tokens(tokens)

print(f"Input: {text}")

print(f"Tokens: {tokens}")

print(f"Token strings: {token_strs}")

print(f"\nBreakdown:")

for token_id, token_str in zip(tokens, token_strs):

print(f" {token_id:6d} -> '{token_str}'")

return tokens

tokenizer = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained("gpt2")

debug_tokenization("strawberry", tokenizer)Consider a model that fails at palindrome detection. You give it “racecar” and “level” and it can’t identify them as palindromes. The problem is tokenization again. “racecar” might split into ["race", "car"]. From the model’s perspective, the question becomes “Are the tokens ‘race’ and ‘car’ reversible?” which is a completely different problem than checking if the character sequence is reversible.

You could work around this by forcing character-level tokenization in your prompts. Instead of “Is racecar a palindrome?”, try “Is r-a-c-e-c-a-r a palindrome?” Each letter becomes a separate token, giving the model the character-level information it needs. This workaround can boost accuracy from 40% to 95% on palindrome tasks.

A model might also struggle with reversing a string. It’s the same fundamental issue. The model doesn’t see individual characters, only tokens. Reversing tokens isn’t the same as reversing characters. If “hello” tokenizes as a single token, the model has no character-level information to reverse. It would need the string spelled out as separate characters: “h-e-l-l-o”.

This is the tradeoff you accept with subword tokenization. You gain compression efficiency and handle rare words gracefully, but you lose fine-grained character access. For most NLP tasks, this tradeoff is worth it. For character-level reasoning tasks, you need to work around it.

What HuggingFace Actually Does

When you call AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained("gpt2"), HuggingFace downloads two files behind the scenes: vocab.json and merges.txt. These files completely define your tokenizer.

The vocab file maps tokens to their integer IDs. This is like your schema, the lookup table that converts token strings to numbers and back. The merges file contains BPE merge rules in the order they were learned during training. These rules define your compression strategy.

Think of it like this: the vocab tells you what tokens exist, and the merges tell you how those tokens were created from smaller pieces. Both files are essential. You can’t use one without the other.

Here’s a simplified version of what’s happening under the hood.

import json

class SimplifiedHuggingFaceTokenizer:

def __init__(self, vocab_path, merges_path):

with open(vocab_path) as f:

self.vocab = json.load(f)

with open(merges_path) as f:

merges = f.read().split('\n')[1:]

self.merges = {}

for i, merge in enumerate(merges):

if merge:

pair = tuple(merge.split())

self.merges[pair] = i

self.id_to_token = {v: k for k, v in self.vocab.items()}

def decode(self, token_ids):

tokens = [self.id_to_token[tid] for tid in token_ids]

text = ''.join(tokens)

return text.replace('Ġ', ' ')This is a simplified interpretation. The real HuggingFace implementation handles edge cases, special tokens, Unicode properly, and uses Rust for performance-critical parts. Tokenization is CPU-bound, so moving the hot path to Rust gives them significant speedups. But conceptually, it’s still BPE with merge rules applied in order.

No magic here 🪄. Just data structures and iteration.

Production Debugging

When weird model behavior shows up in production, tokenization issues are the culprit about 70% of the time. This should be your first check, not your last resort after exhausting every other possibility.

Start with a debugging tool that shows you exactly what tokens the model sees.

class TokenizerDebugger:

def __init__(self, tokenizer):

self.tokenizer = tokenizer

def analyze_text(self, text, max_tokens=None):

tokens = self.tokenizer.encode(text)

token_strs = self.tokenizer.convert_ids_to_tokens(tokens)

report = {

"input_length": len(text),

"token_count": len(tokens),

"tokens_per_char": len(tokens) / len(text),

"tokens": tokens,

"token_strings": token_strs

}

if max_tokens and len(tokens) > max_tokens:

report["warning"] = f"Exceeds limit by {len(tokens) - max_tokens} tokens"

report["truncated_text"] = self.tokenizer.decode(tokens[:max_tokens])

return report

def compare_texts(self, text1, text2):

a1 = self.analyze_text(text1)

a2 = self.analyze_text(text2)

return {

"text1": a1,

"text2": a2,

"efficiency_ratio": a1["tokens_per_char"] / a2["tokens_per_char"]

}

debugger = TokenizerDebugger(tokenizer)

analysis = debugger.analyze_text(

"The patient diagnosed with acute myocardial infarction...",

max_tokens=100

)

if "warning" in analysis:

print(f"⚠️ {analysis['warning']}")

print(f"Truncated: {analysis['truncated_text']}")This debugger does two important things: First, it shows you the actual token breakdown so you can see where your text is getting split. Second, it warns you when you’re about to hit token limits before you waste time debugging phantom issues.

System Prompt Creep

Imagine a chatbot that gradually gets slower over time. Response times drift from 200ms to 2 seconds over three months. No code changes. No infrastructure changes. What’s happening?

System prompt bloat. Product managers keep adding “guardrails” and “safety instructions” to prevent bad outputs. Each addition seems small (10-20 words), but they accumulate. The system prompt grows from 50 tokens to 450 tokens over time. That’s 9x more processing overhead on every single request.

The model spends more time processing the bloated system prompt than actually answering user questions. Refactoring the prompt back down to 80 tokens while maintaining the same functionality would drop response times to 250ms.

⚠️ System prompt creep is real. Review your prompts periodically and cut anything that doesn’t demonstrably change model behavior. Those reassurances like “Be helpful and accurate” sound nice but the model already does that by default.

Multi-Language Token Issues

Consider a translation service that works perfectly in English but times out for Japanese and Arabic. Same context window. Same model. Same code. The only difference is the language.

Tokenization efficiency varies dramatically across languages. English tokenizes efficiently because GPT trained primarily on English text. Japanese and Arabic don’t get the same treatment. The same 1000-character document will use vastly different token counts depending on the language:

- English: 250 tokens

- Japanese: 1200 tokens

- Arabic: 1400 tokens

Japanese and Arabic hit the context window limit while English cruises through with tokens to spare. This creates an invisible performance ceiling that only affects certain languages.

The fix is language-specific token budgets.

LANGUAGE_TOKEN_MULTIPLIERS = {

"en": 1.0,

"es": 1.1,

"fr": 1.1,

"de": 1.2,

"ja": 4.8,

"zh": 3.5,

"ar": 5.6,

"ko": 4.0

}

def calculate_chunk_size(max_tokens, language):

multiplier = LANGUAGE_TOKEN_MULTIPLIERS.get(language, 2.0)

return int(max_tokens / multiplier)

chunk_size = calculate_chunk_size(max_tokens=2000, language="ja")

print(f"Safe chunk size for Japanese: {chunk_size} characters")

# Output: Safe chunk size for Japanese: 416 charactersThese multipliers account for the tokenization inefficiency per language. Instead of chunking all languages at 2000 characters, you adjust based on how each language actually tokenizes. This prevents mysterious timeouts that only happen for specific languages 🌍.

Performance Bottlenecks

Consider a system where tokenization accounts for 40% of total latency. That’s a huge chunk of processing time spent converting text to numbers. If you’re tokenizing the same system prompt on every single request, you’re doing wasteful work.

The fix is caching. Tokenization is a pure function (same input always produces the same output), which makes it perfect for memoization.

from functools import lru_cache

class CachedTokenizer:

def __init__(self, tokenizer):

self.tokenizer = tokenizer

self._encode = lru_cache(maxsize=1000)(self._encode_impl)

def _encode_impl(self, text):

return tuple(self.tokenizer.encode(text))

def encode(self, text):

return list(self._encode(text))

def decode(self, tokens):

return self.tokenizer.decode(tokens)

cached_tokenizer = CachedTokenizer(AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained("gpt2"))

# First call: slow

tokens1 = cached_tokenizer.encode("System prompt here")

# Second call: instant (cached)

tokens2 = cached_tokenizer.encode("System prompt here")This caching approach can give you 20x speedup on repeated text. For RAG systems, you can take this further by pre-tokenizing documents and storing the tokens alongside the original text. That way you never re-tokenize the same document on every query.

Different tokenizer implementations also have dramatically different performance characteristics. HuggingFace’s transformers library is written in Python, which makes it slower for CPU-bound operations like tokenization. OpenAI’s tiktoken library is written in Rust and runs 3-10x faster for the same tokenization task:

import tiktoken

encoding = tiktoken.get_encoding("cl100k_base")

tokens = encoding.encode("Your text here")

decoded = encoding.decode(tokens)The performance difference is dramatic. Tokenizing 1 million documents (averaging 500 words each) takes about 45 minutes with HuggingFace’s GPT2Tokenizer but only 4 minutes with tiktoken’s cl100k_base encoder. That’s more than 10x faster. If you’re doing batch processing or handling high-throughput API requests, switching implementations can save you real money on compute costs.

Common Gotchas

Tokenization has a few quirks that trip people up regularly. These aren’t bugs or design flaws, just behavior you need to be aware of when working with tokenizers in production.

Whitespace Handling

GPT-2 uses a special character (Ġ) to represent spaces at the start of tokens:

from transformers import AutoTokenizer

tokenizer = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained("gpt2")

tokens = tokenizer.tokenize("hello world")

print(tokens)

# Output: ['hello', 'Ġworld']That Ġ isn’t just formatting or a display artifact. It’s actually part of the token representation. The tokenizer uses it to distinguish between “world” at the start of a sentence versus ” world” in the middle of a sentence. If you’re manually manipulating tokens (which you probably shouldn’t do often), you need to preserve these special characters. Strip them out and your decoded text will have missing spaces.

Case Sensitivity

“Hello” and “hello” aren’t the same token.

hello_tokens = tokenizer.encode("hello")

Hello_tokens = tokenizer.encode("Hello")

print(f"'hello': {hello_tokens}")

print(f"'Hello': {Hello_tokens}")

# Different token IDsThis creates a subtle but important problem. If you lowercase all your training data to simplify preprocessing, your model learns associations with the lowercase token IDs. Then you deploy to production and feed it mixed-case text from users. Same words, completely different token IDs. The model’s learned patterns don’t transfer because it’s seeing token 464 (“The”) instead of token 262 (“the”) it trained on.

The fix is consistency. Apply the same case normalization during both training and inference. If you lowercase during training, lowercase at inference. If you preserve case during training, preserve it at inference.

Numbers and Dates

Numbers tokenize inconsistently depending on formatting.

print(len(tokenizer.encode("1000"))) # 1 token

print(len(tokenizer.encode("1,000"))) # 2 tokens

print(len(tokenizer.encode("1 000"))) # 3 tokens

print(len(tokenizer.encode("one thousand"))) # 2+ tokensSame number, wildly different token counts. This creates unpredictable behavior if your data has inconsistent number formatting. Financial reports where some analysts use comma separators and others don’t will have dramatically different token usage for the same data.

Dates are even worse!

date1 = tokenizer.encode("2024-01-15")

date2 = tokenizer.encode("01/15/2024")

date3 = tokenizer.encode("January 15, 2024")

print(f"ISO format: {len(date1)} tokens")

print(f"US format: {len(date2)} tokens")

print(f"Written format: {len(date3)} tokens")ISO format might use 3 tokens, US format uses 5 tokens, written format uses 6 tokens. If you’re working with tight context windows, this variation can be the difference between fitting your document or hitting the limit. Normalize to ISO 8601 (YYYY-MM-DD) before tokenization and stick with it.

URLs and Emails

URLs get fragmented aggressively.

url = "https://www.example.com/api/v2/users/12345/profile"

tokens = tokenizer.encode(url)

print(f"URL tokens: {len(tokens)}")

print(tokenizer.convert_ids_to_tokens(tokens))

# 15+ tokens for one URLEvery slash, period, and path segment becomes a separate token. If you’re building systems that process social media posts or web content, URLs can consume a surprising portion of your token budget. A tweet with 2-3 URLs can use 30-40% more tokens than the same tweet without URLs.

Replace URLs with placeholder tokens for better efficiency.

import re

text_with_url = "Check out https://www.example.com/very/long/path for details"

cleaned_text = re.sub(r'https?://[^\s]+', '[URL]', text_with_url)

tokens = tokenizer.encode(cleaned_text)

# Much fewer tokensYou can get fancy with domain-specific placeholders too. [URL_ARXIV], [URL_GITHUB], [URL_YOUTUBE] preserve some semantic information (that it’s a research paper vs code repository vs video) while still compressing token usage.

Email addresses have the same problem. The @ symbol and domain names fragment poorly.

email = "john.doe@example-company.com"

tokens = tokenizer.encode(email)

print(f"Email tokens: {len(tokens)}")

# Might be 8-10 tokens for one email addressReplace with [EMAIL] or domain-specific placeholders like [EMAIL_INTERNAL] vs [EMAIL_EXTERNAL] depending on your use case.

Emojis

Emojis are particularly inconsistent 😅.

emoji_text = "I love Python! 🐍💻"

tokens = tokenizer.encode(emoji_text)

token_strs = tokenizer.convert_ids_to_tokens(tokens)

print(token_strs)

# Emojis might be 1 token or split into byte tokensWhether emojis become single tokens or split into multiple byte-level tokens depends on how the tokenizer was trained. Some common emojis like 😂 and ❤️ might be single tokens because they appeared frequently in training data. But less common emojis like 🎉 or 🥳 might split into multiple byte tokens.

This creates problems for sentiment analysis on social media text where emojis carry significant semantic meaning. A tweet like “Just got the job! 🎉🥳” has clear positive sentiment, but if the celebration emojis are fragmented across multiple byte tokens, the model might not pick up on their meaning as effectively as it would with single-token emojis.

This is also why models trained on Twitter data often perform poorly on formal business emails. The token distributions are completely different. Twitter has emojis, hashtags, mentions (#ML, @user), shortened URLs, and informal language.

Business emails have formal vocabulary like “pursuant”, “heretofore”, and “cc:” that rarely appear in social media training data. The tokenization is fixed, but the token distribution shifts dramatically between domains. Your model learned associations with one set of tokens and now sees a completely different set in production.

For domain-specific applications, custom tokenizers trained on your target domain help significantly. But if the domains are wildly different (like Twitter vs legal documents), you might be better off training separate models rather than trying to force transfer learning 🤷🏾♀️.

Tokenization issues are everywhere once you start looking for them. The token tax. Version mismatches. Domain-specific vocabulary burning through your token budget. These problems don’t announce themselves with error messages. They just make your model quietly perform worse.

The strawberry problem went viral for a reason; it’s a perfect example of how tokenization limitations create unexpected failures. But now you know why it happens and how to debug it.

Next time your model outputs garbage, check the tokens first. Verify vocabularies. Calculate your actual token budget. Don’t assume the advertised context window is what you can actually use.

Will you still make tokenization mistakes? Probably. I still do sometimes 😅. But you’ll recognize them faster and fix them more efficiently.

Happy coding 💻