Part 2 of the “LLM Production Pipeline” Series

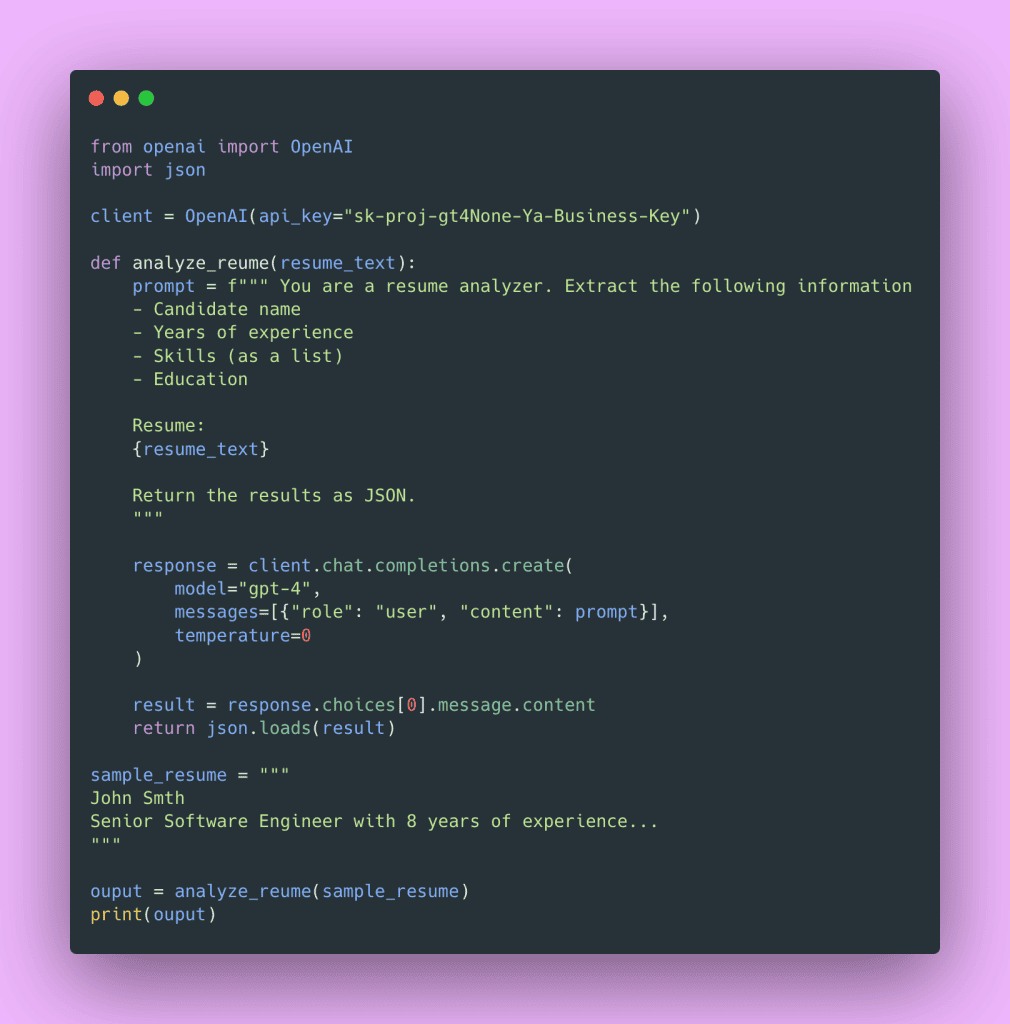

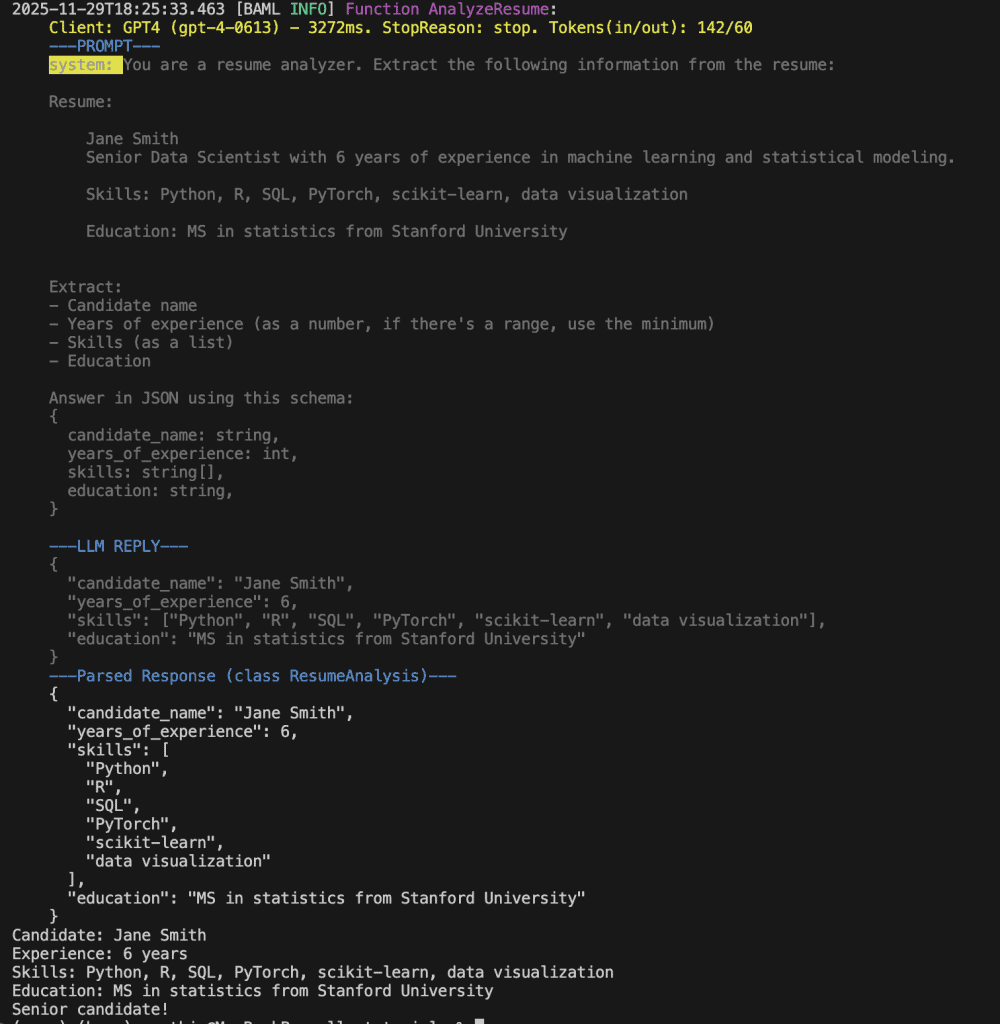

A week after that sprint planning meeting where I couldn’t estimate my LLM work, I thought I’d gotten my act together. I’d refactored the prompt string into a function, moved the API key to an environment variable, and felt pretty accomplished. Then I ran the code on a new batch of resumes.

It crashed.

My downstream processing code expected years_of_experience to be an integer. The LLM returned “5-7 years” for someone with a range on their resume. My code that did if years_of_experience > 3 threw a TypeError and took down the whole pipeline.

This wasn’t an LLM problem. My code had no way to enforce what the LLM should return. I was hoping it would always give me an integer. When it didn’t, I had no safety net.

That search for a better approach led me to BAML.

The Two Problems We’re Fixing

From Part 1, we’re tackling two specific issues 👇🏾.

No type safety. We don’t know what our LLM functions return. Is it a dict? What keys? What types? Your IDE can’t help you, and you won’t find out until runtime.

String manipulation chaos. Our prompts are scattered f-strings buried in functions. We can’t version them, can’t reuse them easily, can’t A/B test them methodically.

I’m showing you BAML because it solves these problems elegantly. But the principles (type safety, separation of concerns, treating prompts as first-class citizens) matter more than any specific tool. If BAML disappeared tomorrow, you could apply these same principles with other tools.

What BAML Does

BAML comes from Boundary ML. It stands for Basically a Made-up Language.

Here’s how BAML works: you define your prompts and their expected output schemas in a separate .baml file. BAML generates type-safe Python (or TypeScript) code. Your IDE knows what types you’re working with. You get autocomplete. You get actual contracts that the LLM needs to fulfill.

The alternative? What we did in Part 1. Hope that your string manipulation produces valid prompts and that the LLM returns something usable.

When I first heard about BAML, I thought “do we really need a new language just for prompts?”

But it’s not about the language syntax. It’s about having a place where prompts live separately from your application code. When your prompts are scattered across ten different Python files as f-strings, nobody knows which version runs in production. BAML forces you to put them all in one place, give them types, and version them properly.

Could you do this without BAML? Sure. But you probably won’t because it’s annoying to set up from scratch.

Installing BAML

Assuming you’ve got Python 3.9 or higher, run pip install baml-py.

If you use VSCode, grab the BAML extension from the marketplace. The syntax highlighting alone is worth it, but you also get inline validation that catches errors before you run the code.

Converting Our Messy Notebook to BAML

Remember the janky resume analyzer from Part 1?

The biggest issue: we’re treating the prompt like a throwaway string, and we don’t know what structure that JSON will have when it comes back.

Creating a BAML File

First, set up your project structure.

my-llm-project/

├── baml_src/

│ └── resume.baml

├── main.py

├── .env

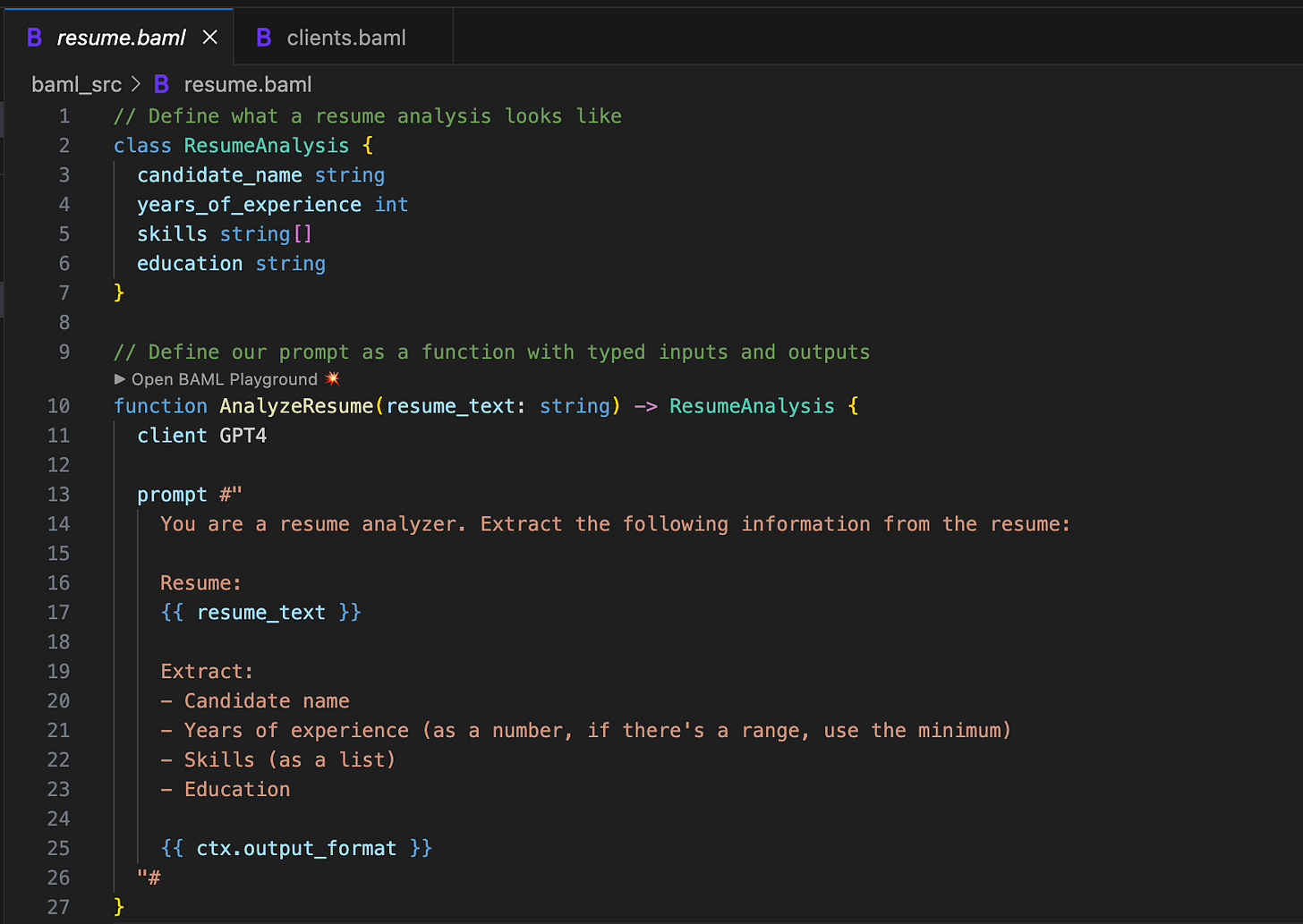

└── requirements.txtInside baml_src/resume.baml, define your types and prompt function.

We defined a class ResumeAnalysis. This is our schema and our contract. When this function runs, it will return an object with these fields and these types. Not “hopefully returns” or “usually returns”. Will return.

Notice I added a clarification in the prompt: “if there’s a range, use the minimum.” Remember my crash? This prompt clarification prevents that crash. We’re explicit about what we expect.

The {{ ctx.output_format }} at the end is BAML magic. It automatically generates the JSON schema instructions for the LLM based on your class definition. You don’t have to manually write “return this as JSON with these exact fields.” BAML handles that for you.

{{ variable_name }} for variable interpolation, not Python’s f-string style.

Configuring Your LLM Client

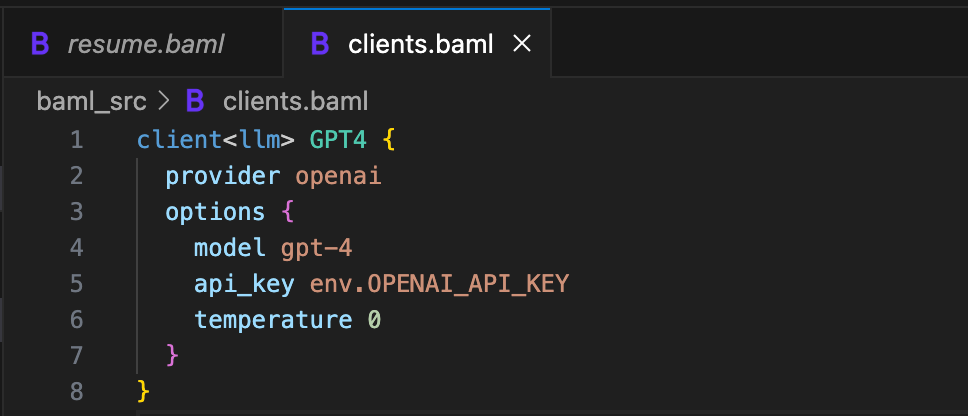

Before our function works, we need to tell BAML how to call GPT-4. Create another file in baml_src/ called clients.baml.

We separated the configuration (which model, which API key, what temperature) from the function definition. This is separation of concerns in action. If you want to swap GPT-4 for GPT-5, or switch to a different provider entirely, you can change it in one place. Your function definitions don’t need to know or care about which model runs.

Generating the Python Code

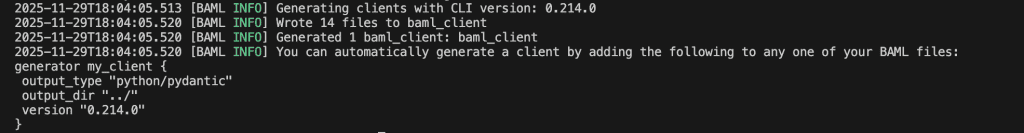

Run the BAML compiler.

baml-cli generate

This creates a baml_client/ directory with generated Python code. Don’t edit these files manually (they’ll get overwritten next time you run the generator), but do check them into version control.

Using It in Your Python Code

Open up main.py.

Look at what we just did.

analysis.candidate_name – Your IDE knows this exists.

analysis.years_of_experience – Your IDE knows this is an int.

analysis.skills – Your IDE knows this is a list of strings.

If you try to access a field that doesn’t exist, your IDE yells at you before you run the code. If you try to do math on candidate_name, your type checker catches it.

This is type safety.

Handling Complex Nested Structures

The resume analysis returns flat data: a name, a number, a list of strings. Most real-world LLM tasks aren’t that simple.

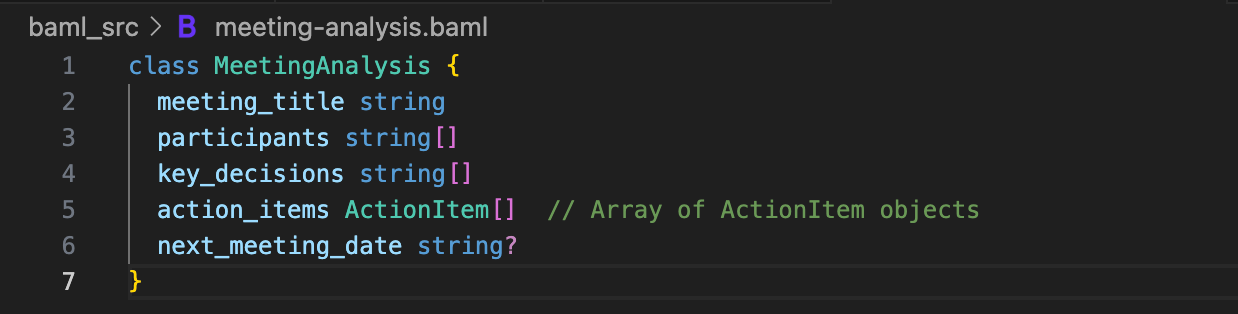

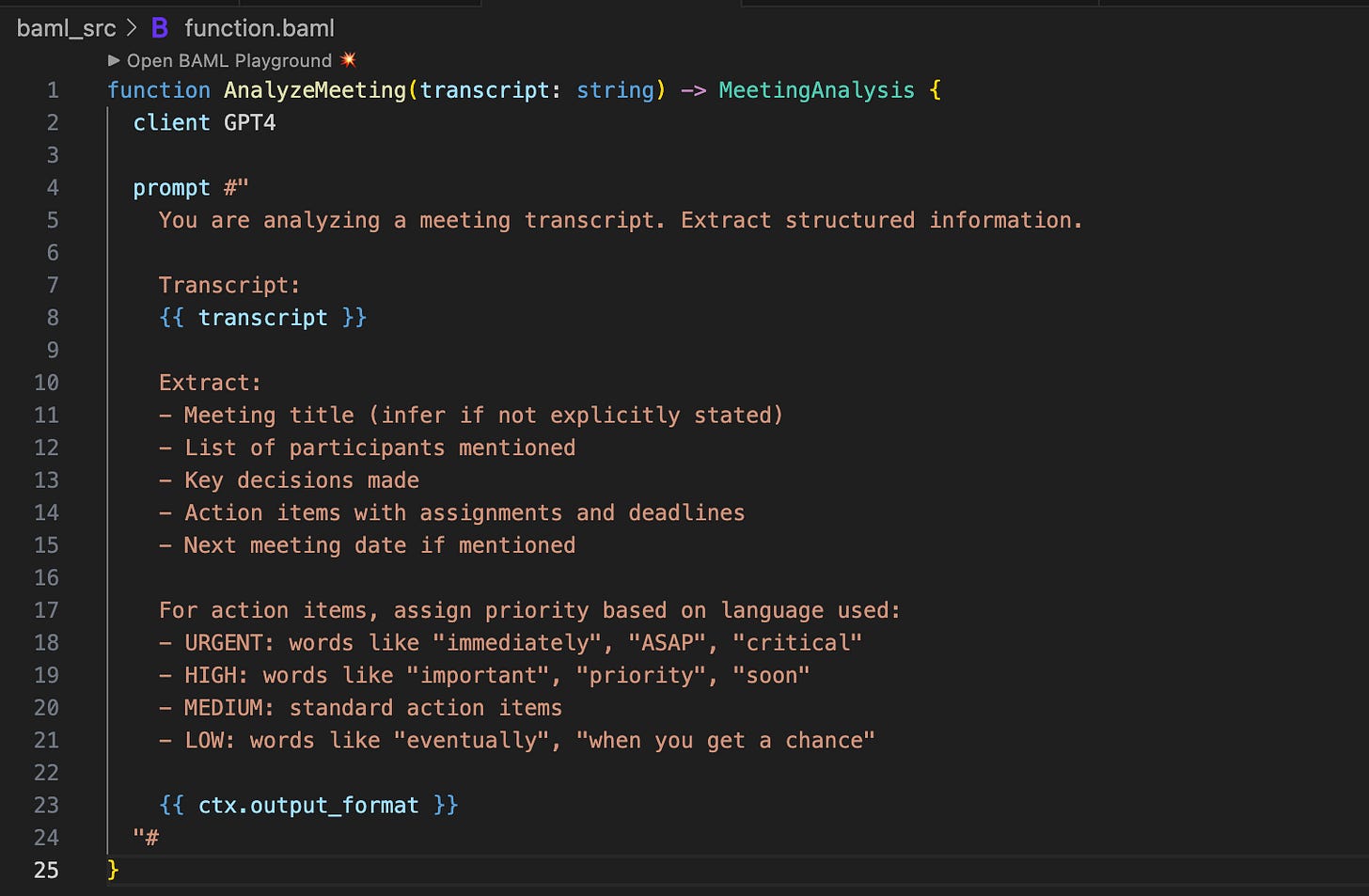

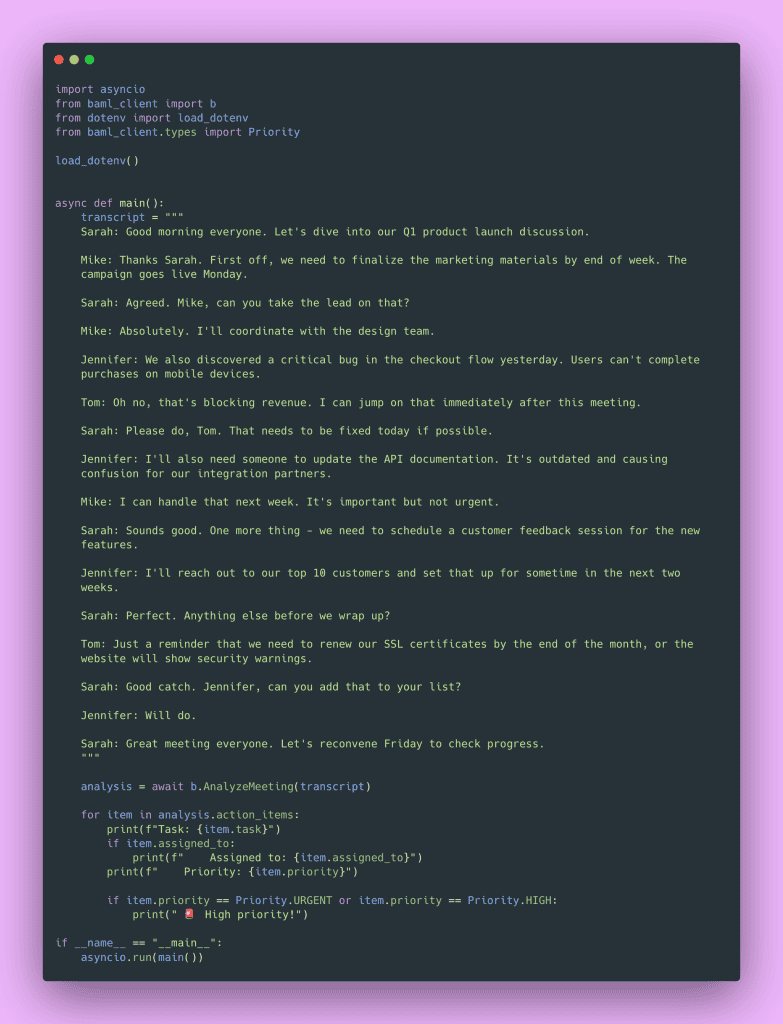

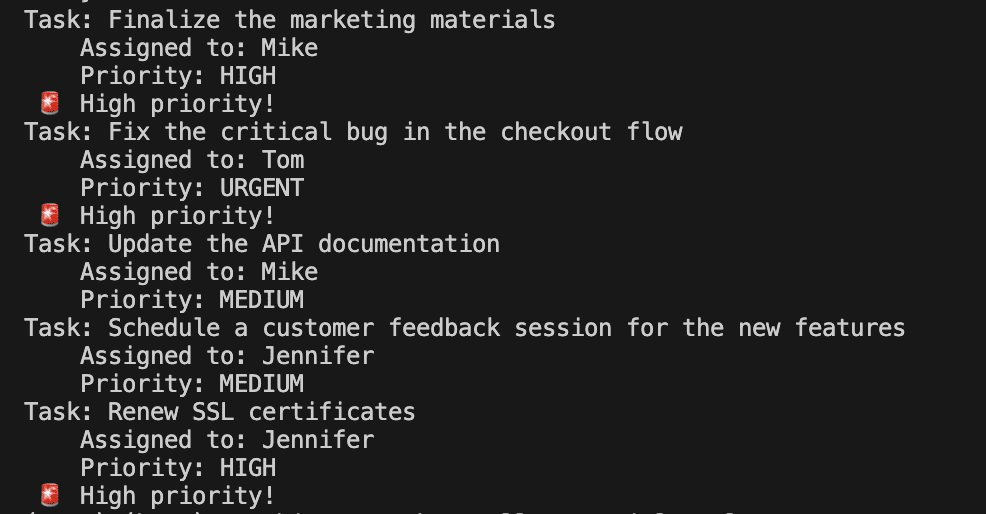

Say you’re analyzing meeting transcripts. You need action items, but each action item has its own structure: a task, who it’s assigned to, a due date, a priority level. That’s nested data.

Here’s how you handle it in BAML. First, define the nested structure.

Each action item is its own object with typed fields. The Priority enum ensures the LLM can only return those four values, not random strings like “kinda important”.

Now define what a full meeting analysis looks like.

The action_items field is an array of ActionItem objects. Your IDE understands this nesting.

Here’s the function 👇🏾

Using it in Python.

Your IDE knows item is an ActionItem. It knows item.priority is a Priority enum. You get autocomplete for nested fields.

Configuration Management Done Right

Remember that security nightmare of hardcoded API keys from Part 1? BAML handles this properly.

You can define multiple clients for different scenarios:

client<llm> GPT4 {

provider openai

options {

model gpt-4

api_key env.OPENAI_API_KEY

temperature 0

}

}

client<llm> GPT5 {

provider openai

options {

model gpt-5-mini

api_key env.OPENAI_API_KEY

temperature 0

}

}

client<llm> Claude {

provider anthropic

options {

model claude-3-sonnet-20240229

api_key env.ANTHROPIC_API_KEY

temperature 0

}

}And in your function definition, you specify which client to use.

Want to test if Claude gives better results? Change one word. Want to swap out the model for a locally hosted one? Define a new client, point it at your local endpoint, change one word in your function. The rest of your Python code doesn’t change.

This is proper abstraction. You’ve separated what you want to do (analyze a resume) from how you’re doing it (which model, which provider).

I usually start with gpt-4.1-nano for development and testing because it’s cheaper. Once the prompts work well, I switch to gpt-4.1 for production. With BAML, that’s a one-word change in the client configuration.

The Principles Matter More than the Tool

BAML could disappear tomorrow and these lessons would still be valuable.

What matters:

- Type safety: Define schemas for your LLM outputs and enforce them.

- Separation of concerns: Keep prompts separate from application logic.

- Testability: Make it possible to test your prompts in isolation.

- Versioning: Treat prompts as code that can be versioned and reviewed.

- Configuration management: Separate what you’re doing from how you’re doing it.

You could implement these principles with Pydantic models for type safety, a custom prompt management system, a simple YAML file for prompts, or your own abstraction layer.

BAML makes it easier. But if you walk away from this thinking “I need to use BAML,” you’ve missed the point. Walk away thinking “I need type safety and structure for my LLM applications,” then choose whatever tool helps you get there.

Before BAML, I tried building my own prompt management system with Pydantic. It worked okay, but it was a lot of boilerplate code. BAML handles all that boilerplate for you, which is why I switched. But the underlying principles (schemas, separation of concerns, testability) were the same.

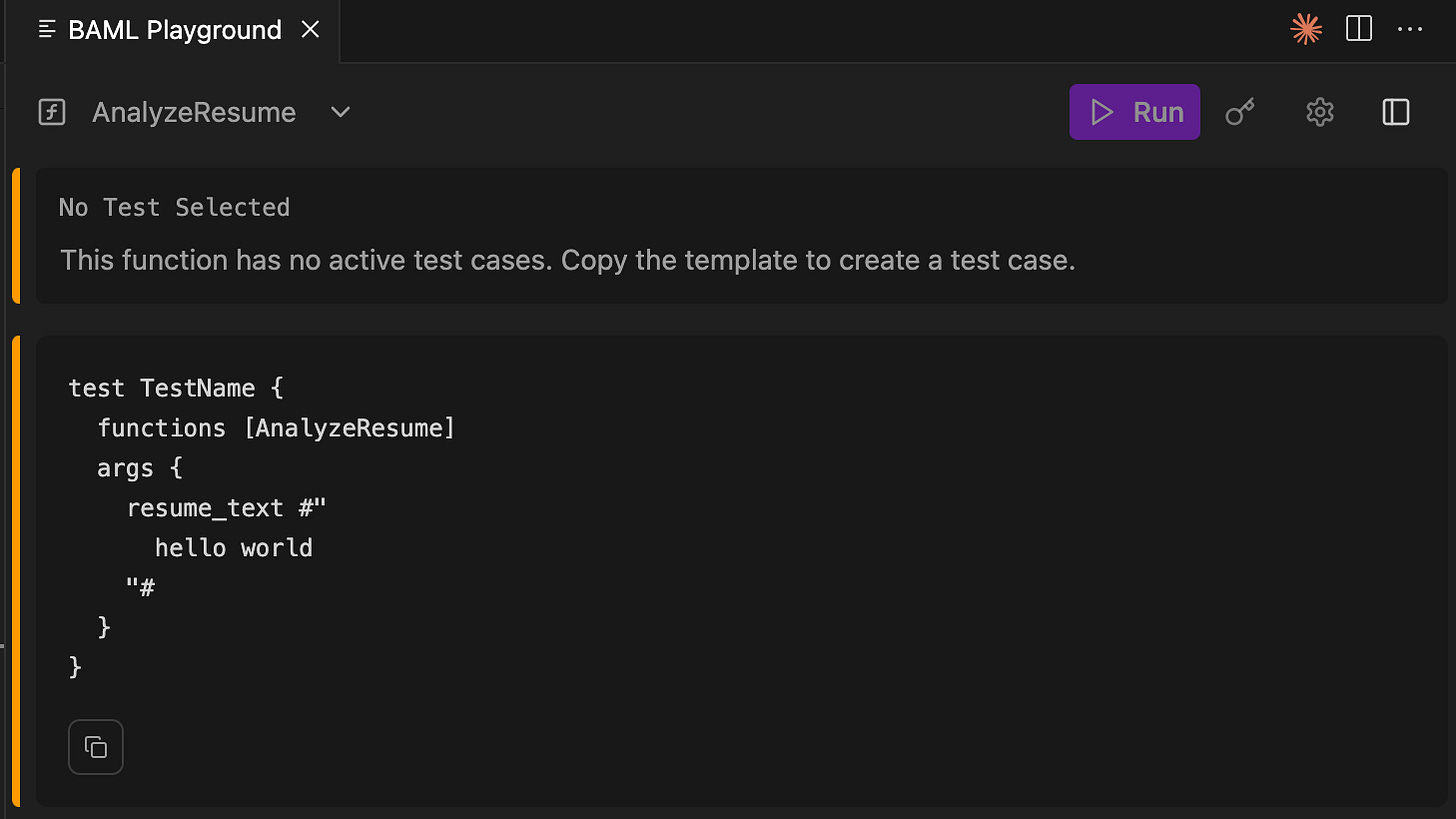

The VSCode Playground

One more thing about BAML: the VSCode extension gives you a playground where you can test your prompts without running your entire application.

You can click on a function in your .baml file, click “Test in Playground,” and try it out with different inputs. Instead of modifying your prompt, running your Python script, waiting for the API call, checking the output, repeat…you test right there in VSCode.

The first time I used this, I saved myself 30 minutes of iteration time. I was tweaking a prompt to get the output format right, and being able to test it directly in VSCode without context-switching to my terminal made a massive difference.

Exercise: Try Converting One Prompt

Pick one prompt from your codebase. Just one.

Install BAML (pip install baml-py), create a baml_src directory, define the output schema as a BAML class, convert the prompt to a BAML function, generate the Python code, and replace your old implementation with the new type-safe version.

When you define that output schema, you’ll probably realize your prompt was underspecified. You’ll find yourself adding clarifications like “if there’s a range, use the minimum” or “return dates in ISO format.” This is good. This is you thinking more carefully about what you actually want the LLM to do.

I’ve done this with probably a dozen prompts, and every time I realize my original prompt was vaguer than I thought. The act of defining a schema forces you to be explicit about your expectations.

In the next post, we tackle testing. Now that we have type-safe, well-structured prompts, we can test them properly. We’ll cover mocking, test doubles, and how to build a comprehensive test suite without calling the OpenAI API a thousand times (and racking up a ridiculous bill).

Happy coding 👍🏾