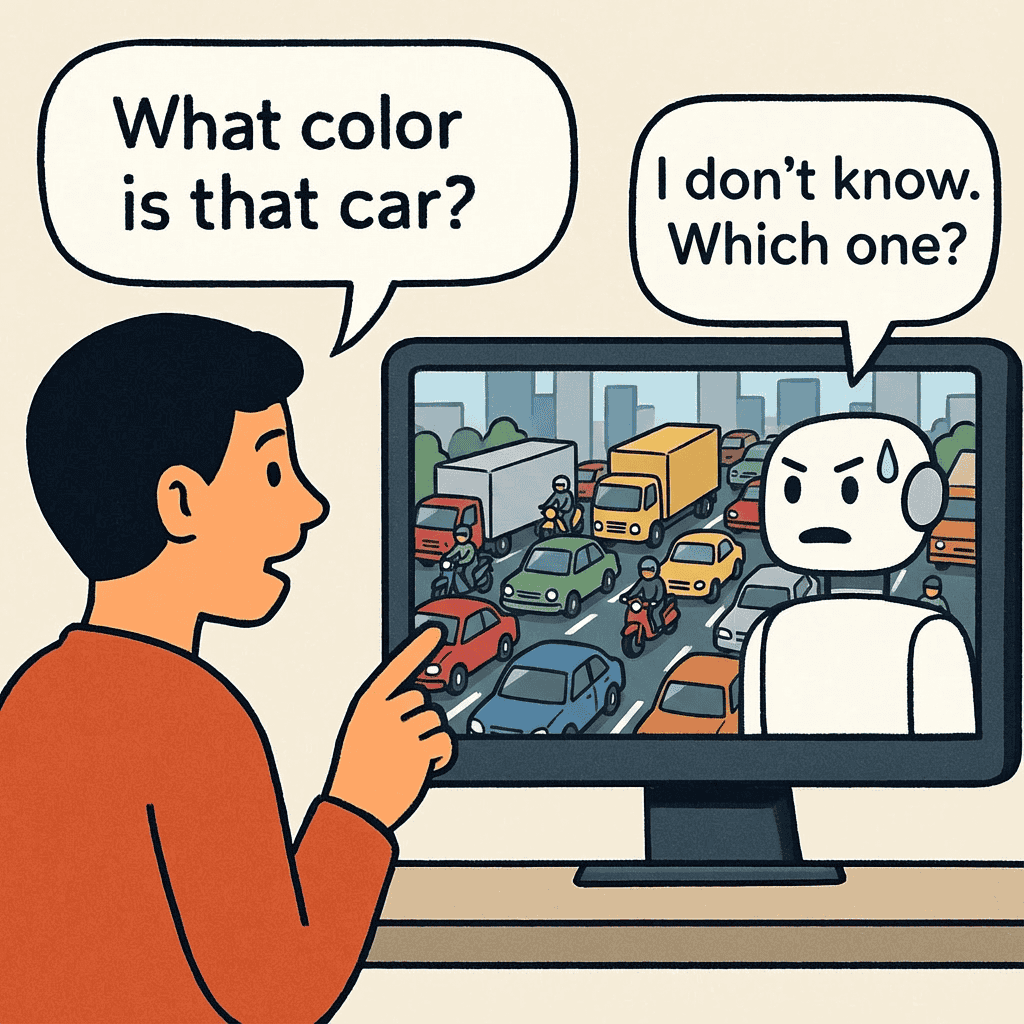

Vision-language models have gotten really powerful lately, but there’s a fundamental problem when you try to use them for spatial reasoning. Upload an image with five cars and ask “What color is that car?” The model has no clue which one you’re talking about. It might describe all of them, pick randomly, or get confused and give you vague nonsense.

You could try being more descriptive: “the red car on the left side near the building.” Now the model has to understand relative positions, colors, spatial relationships, and landmarks all at once. That’s asking a lot, and the results are hit or miss.

Microsoft’s Magma8B solves this with Set-of-Mark (SoM) prompting. You draw numbered boxes directly on the image. Instead of vague spatial descriptions, you mark the car as #1 and ask “What color is object #1?” The model understands these visual markers because it was specifically trained on them. No ambiguity, no confusion.

I’m walking you through building a complete client-server API using Magma8B. You’ll learn how to serve an 8-billion parameter vision model, handle image encoding over HTTP, implement proper error handling, and structure code that doesn’t fall apart when things go wrong. The software engineering patterns here apply whether you’re serving ML models, building microservices, or designing any distributed system.

This post will separate you from the other machine learning engineers or data scientists who can only get a model working in a Jupyter notebook. By the end of this article, you’ll walk away knowing how to build a system that handles real requests.

What You Need to Know

You should be comfortable with Python classes and functions. REST APIs should make sense at a basic level. If you’ve used requests.get() and understand what HTTP status codes mean, you’re fine. Some understanding of neural networks helps, but you don’t need to derive backpropagation or understand gradient descent in depth.

Docker knowledge isn’t required for this part. We’ll cover containerization and deployment in Part 2.

Understanding Set-of-Mark Prompting

Traditional visual question answering (VQA) systems struggle with spatial references. They can tell you what’s in an image, but when you need to point at something specific and ask about that exact thing, they don’t have a reliable mechanism to understand your reference.

Set-of-Mark prompting changes this by making spatial references explicit. Here’s how it works:

- Add visual markers to your image (numbered bounding boxes, highlights, or tags)

- The model processes both the marked image and your text prompt

- Reference specific markers in your text: “What is object #3 doing?”

- The model grounds its response in the marked regions

The model learned to associate text references like “#3” with visual regions during training. When you ask about “#3”, the model knows exactly which part of the image you mean.

This isn’t just a clever prompt engineering trick. Magma8B was trained on millions of images with Set-of-Mark annotations. The model’s weights encode the relationship between numeric references in text and visual markers in images. You can’t just take any vision-language model and expect it to understand marked images.

Real-World Applications

Set-of-Mark prompting unlocks some practical use cases.

Document Analysis: When working with scanned documents, you can mark specific paragraphs or sections. “Summarize paragraph #3” becomes unambiguous. Legal document review, contract analysis, and research paper summarization all benefit from this precision.

UI Testing: Automated testing frameworks can mark specific UI elements. “Click button #2” gives you maintainable tests that don’t break when the UI layout changes slightly.

Robotics: Pick-and-place tasks become more reliable. “Grasp object #1” tells the robot exactly which object to target, even in cluttered environments.

Medical Imaging: Radiologists can mark regions of interest and ask specific questions. “Analyze the tissue marked as #1” focuses the model’s attention on the relevant area.

The key advantage is precision. Spatial references are explicit rather than implicit, reducing errors and making the system’s behavior predictable.

Understanding Magma8B 🤖

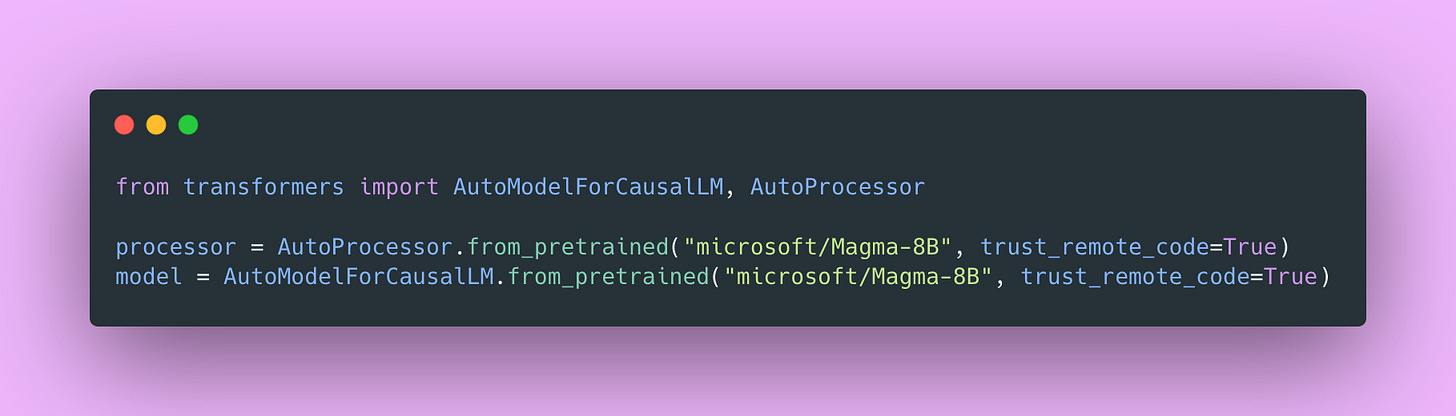

Magma8B is Microsoft’s vision-language-action model released in February 2025. It has 8 billion parameters and combines a CLIP-ConvNeXt-XXLarge vision encoder with Meta’s Llama-3 language model.

What makes Magma significant is that it’s the first foundation model designed specifically for multimodal AI agents!

Most vision-language models stop at understanding. They describe images or answer questions about them. Magma goes further. It generates goal-driven visual plans and actions. The same model that answers ‘What color is object #1?’ can tell a browser to click the search button or generate gripper coordinates for a robot arm.

In Microsoft’s benchmarks, Magma is the only model that performs across the full task spectrum: visual QA, UI navigation, and robotics manipulation. GPT-4V can’t control a robot arm. OpenVLA can’t answer questions about charts. Magma does both.

The architecture has three main components:

Vision Encoder: CLIP-ConvNeXt-XXLarge, trained by the LAION team on billions of image-text pairs. It processes images into visual tokens that capture colors, shapes, textures, spatial relationships, and the visual markers you add.

Language Model: Meta’s Llama-3-8B-Instruct serves as the backbone. It processes both text tokens and visual tokens together. This is where reasoning happens.

Training Data: Microsoft trained Magma on a mix of generic image and video data (LLaVA-Next, ShareGPT4Video), instructional videos (Ego4D, Epic-Kitchen), robotics manipulation data (Open-X-Embodiment), and UI grounding data (SeeClick). The diversity matters; it’s why the model generalizes across such different tasks.

Set-of-Mark isn’t something you can apply to just any vision model. It’s specific to how Magma was trained. Microsoft introduced two techniques during training:

Set-of-Mark (SoM): For static images, objects are labeled with visual markers. The model learned to ground its responses to specific marked regions.

Trace-of-Mark (ToM): For videos, object movements are tracked over time. This helps with action planning and understanding temporal dynamics.

We’re focusing on Set-of-Mark for static images. Trace-of-Mark is powerful for video and robotics data, but that’s beyond scope here.

This doesn’t mean you can’t learn from it or build prototypes. It means you need to understand its limitations:

- The model was trained primarily on English text

- It can perpetuate stereotypes or produce inappropriate content

- It has common multimodal model limitations around hallucination

- It hasn’t been extensively safety-tested for production use

For learning, experimentation, and non-critical applications, Magma8B is excellent. For production systems handling sensitive data or critical decisions, you’d want a model with more extensive safety testing and production support.

Why Client-Server Architecture Matters

Running this model directly in your application isn’t practical for several reasons.

The model checkpoint is 16GB. You’re not shipping that to mobile devices or embedding it in web applications. Inference needs a GPU with at least 24GB of VRAM. Most consumer laptops don’t have that. Loading the model takes several seconds on a good machine, longer on slower hardware. You don’t want users waiting that long on first launch.

Model updates become a nightmare. If you need to fix a bug, you’ll need to push to every client. If you need to upgrade to a newer version, you’ll need to update every installation. How about using a different model? You’ll need to rebuild and redistribute your entire application.

Client-server architecture solves these problems.

- Load the model once on a server with proper GPU resources

- Clients send images and prompts over HTTP

- Server runs inference and returns results

- Clients are lightweight and model-agnostic

This separation means you can upgrade the model, switch to an entirely different architecture, scale to multiple GPUs, or add caching without changing a single line of client code.

The architecture looks like this

Client (Python/JS/Mobile) → API Server (FastAPI) → Model Server (Magma8B on GPU)The API server handles HTTP requests, validates inputs, manages authentication (if needed), and orchestrates inference. The model server focuses solely on loading the model, running inference, and managing GPU memory. Each component has one job and does it well.

Separation of Concerns

This follows a fundamental software engineering principle. Your API layer handles authentication, rate limiting, and logging without touching model code. Your model code focuses exclusively on inference. Want to swap models? Change one file. Want to add API key validation? Modify only the API layer.

You see this pattern everywhere in well-designed systems.

- Web applications separate frontend, backend, and database layers

- Microservices split functionality across independent services

- Operating systems separate kernel space from user space

Network Boundaries Force Good Design

Building across network boundaries actually makes you write better code because it forces constraints.

You must serialize data: Can’t pass Python objects over HTTP. This forces you to think carefully about your data structures and interfaces.

You must handle errors explicitly: Networks fail. Requests time out. Servers crash. You can’t pretend these won’t happen.

You must define clear interfaces: Ambiguous interfaces break quickly over network boundaries. Clear contracts become essential.

You must think about performance: Network latency matters. You optimize data transfer and response times.

These constraints push you toward maintainable, robust code. This is why microservices (despite their complexity) can lead to better system design. The boundaries force discipline.

Building the Model Server

Let’s start with proper project structure. Good organization makes debugging easier and helps others (including future you) understand your code.

magma-api/

├── server/

│ ├── __init__.py

│ ├── main.py # FastAPI application

│ ├── model.py # Model loading and inference

│ ├── schemas.py # Pydantic models for validation

│ └── config.py # Configuration management

├── client/

│ └── client.py # Python client library

├── requirements.txt

├── .env # Local environment variables (add to .gitignore!)

└── README.mdEach file has a single responsibility. The API code lives in main.py, model logic in model.py, validation schemas in schemas.py, and configuration in config.py. This separation makes testing easier and changes more localized.

Create requirements.txt:

fastapi==0.104.1

uvicorn[standard]==0.24.0

torch==2.1.0

transformers==4.35.0

Pillow==10.1.0

pydantic==2.5.0

python-multipart==0.0.6Quick breakdown of dependencies 🕸️

- FastAPI and Uvicorn: Web framework and ASGI server. FastAPI gives you automatic validation, documentation, and excellent async support.

- PyTorch and Transformers: Model inference. Transformers make loading Hugging Face models straightforward.

- Pillow: Image processing for loading and manipulating images.

- Pydantic: Data validation. This will save you from so many bugs.

- python-multipart: File upload support for when we extend the API.

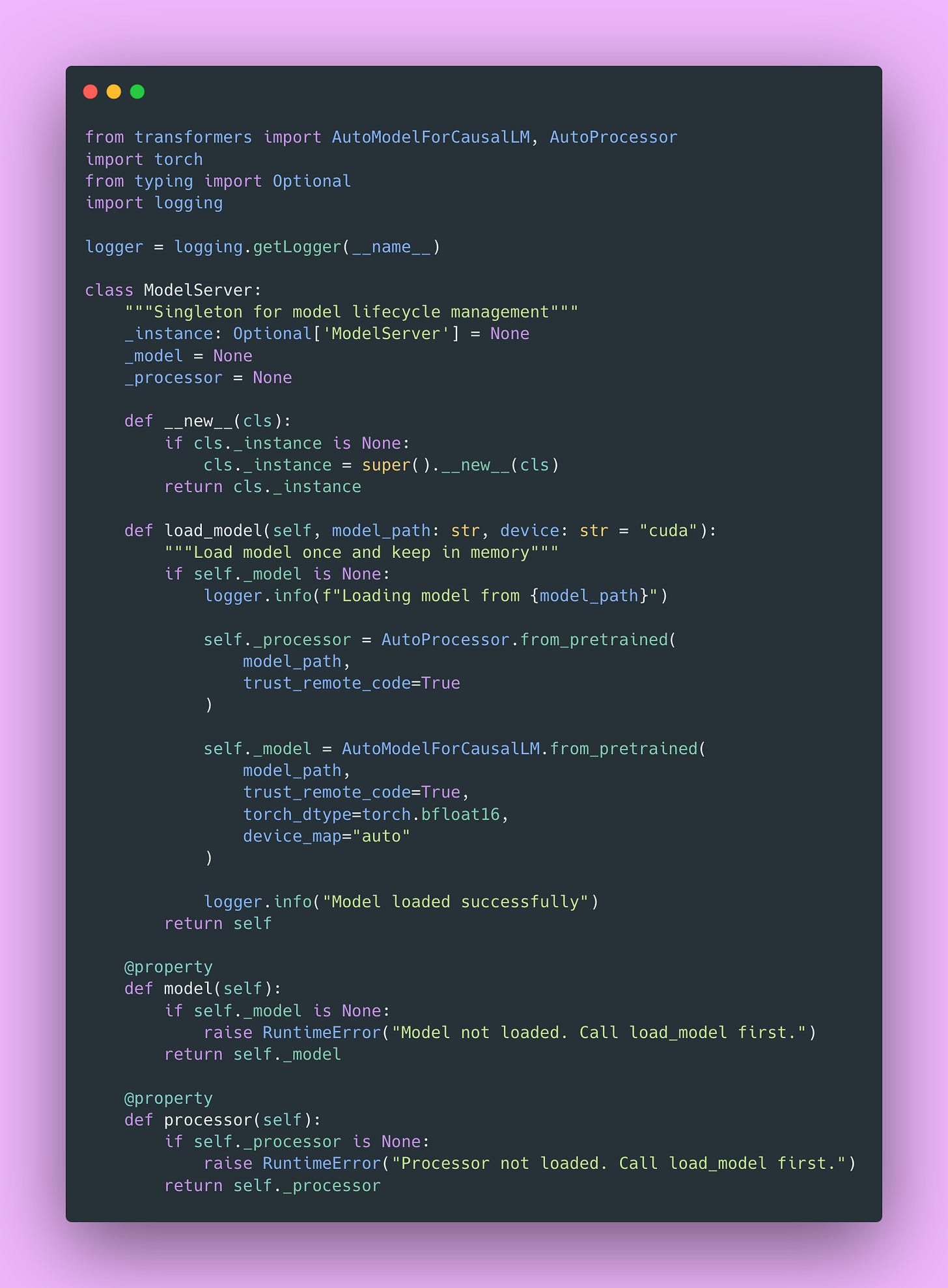

Model Loading and Management

Loading a 16GB model takes time, consumes significant memory, and you definitely don’t want to reload it for every request. That would be painfully slow and waste resources.

The solution is the Singleton pattern. Load the model once, keep it in memory, reuse it for every request. This is standard practice for serving ML models.

Create server/model.py:

Understanding the Singleton Pattern

The __new__ method controls instance creation in Python. Most classes use the default implementation, but we override it to ensure only one instance ever exists.

First time you create ModelServer(), Python creates a new instance and stores it in cls._instance. Every subsequent call checks if _instance exists and returns it if so. One model in memory, shared across all requests.

Why does this matter? If you loaded a new model for every request:

- You’d wait several seconds per request (terrible user experience)

- You’d run out of GPU memory immediately (each model copy takes 16GB)

- You’d waste compute resources loading the same weights repeatedly

The Singleton pattern is common in production systems for expensive resources:

- Database connection pools (one pool, many connections)

- Configuration managers (one config object, accessed everywhere)

- Logger instances (one logger per module)

- Cache managers (one cache instance, shared state)

Memory Optimization with bfloat16

torch_dtype=torch.bfloat16This cuts memory usage in half compared to float32. Instead of 32-bit floating point numbers, we use 16-bit Brain Float format.

“Wait, doesn’t that hurt accuracy?” Not really for inference. Training needs float32 (or even float64 sometimes) for stable gradients across many iterations. Inference runs once through the network, and bfloat16 precision is usually sufficient.

The memory savings are massive. With bfloat16, Magma8B fits comfortably in 24GB of VRAM. With float32, you’d need closer to 32GB. This is standard practice in production ML serving.

Device Mapping

device_map="auto"This tells Transformers to automatically distribute the model across available devices. If you have multiple GPUs, it can split layers across them. If your model barely fits in GPU memory, it can offload some layers to CPU memory (slower, but better than crashing).

For most cases with a single 24GB GPU, this just loads everything onto CUDA device 0.

Property Decorator for Clean Access

@property

def model(self):

if self._model is None:

raise RuntimeError(”Model not loaded. Call load_model first.”)

return self._modelThis creates a clean access pattern with built-in validation. Instead of accessing _model directly, you use model_server.model. If someone tries to use the model before loading it, they get a clear error message:

RuntimeError: Model not loaded. Call load_model first.Much better than:

AttributeError: ‘NoneType’ object has no attribute ‘generate’Good error messages save hours of debugging. When something goes wrong, you want to know exactly what and where.

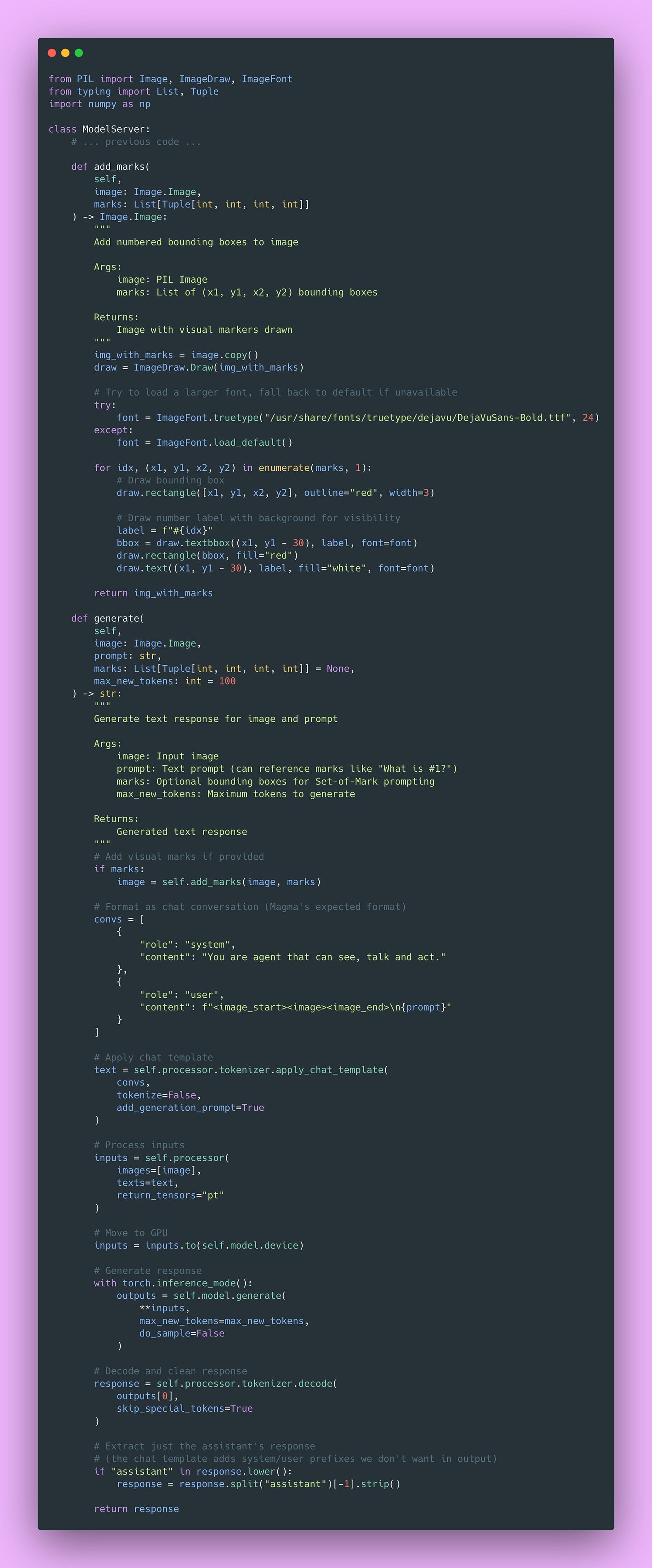

Implementing Set-of-Mark Inference

Now let’s add the actual inference logic. This is where Set-of-Mark prompting happens.

Add to server/model.py:

Drawing Visual Marks

The marks get drawn directly on the image. This is crucial: the model needs to see them to understand references like “#1.” We’re modifying the visual input, not just adding metadata.

draw.rectangle([x1, y1, x2, y2], outline=”red”, width=3)

draw.text((x1, y1 - 30), label, fill=”white”, font=font)We draw red bounding boxes with 3-pixel width for visibility. The label goes above the box with a red background, making it stand out even on complex images.

During training, Magma saw similar visual markers. It learned to associate these visual cues with text references. When you ask “What is object #1?”, the model looks for the visual marker labeled “#1” and reasons about that specific region!

Chat Template Format

Magma expects inputs in a specific chat format:

convs = [

{”role”: “system”, “content”: “You are agent that can see, talk and act.”},

{”role”: “user”, “content”: “<image_start><image><image_end>\nWhat is #1?”}

]The system message sets the context. The user message includes special tokens <image_start> and <image_end> that tell the model where the image embedding goes.

The apply_chat_template method formats these messages according to Llama-3’s conversational structure. Different models have different templates, and Transformers handle this automatically.

Tensor Processing

inputs = self.processor(images=[image], texts=text, return_tensors=”pt”)

inputs = inputs.to(self.model.device)The processor handles several transformations:

- Resizes the image to the expected dimensions (typically 224×224 or 384×384)

- Normalizes pixel values to the range the model expects

- Converts everything to PyTorch tensors

- Tokenizes the text into token IDs

Moving to the model’s device is essential. The model lives on GPU, and mixing CPU and GPU tensors causes errors fast.

Inference Mode

with torch.inference_mode():

outputs = self.model.generate(...)This is better than torch.no_grad() for inference. It disables gradient computation and enables inference-specific optimizations. Always use this for production serving.

Without this context manager, PyTorch tracks gradients for every operation (in case you want to do backpropagation). This uses significant memory and slows things down. For inference, you never need gradients.

Deterministic Generation

do_sample=FalseThis makes generation deterministic. The model always picks the highest probability token at each step. Same input gives same output.

For analytical queries like “What color is object #1?”, you want consistent results. The answer shouldn’t randomly vary between “red”, “crimson”, and “burgundy” depending on sampling randomness.

If you wanted creative or varied outputs (like for creative writing), you’d set do_sample=True and adjust temperature. But for analytical tasks, deterministic output makes sense.

Autoregressive Generation

The generate method works autoregressively:

- Model generates one token

- Appends it to the input

- Generates the next token based on all previous tokens

- Repeats until reaching

max_new_tokensor an end-of-sequence token

This is why generation can be slow for long responses. Each token depends on all previous tokens, so you can’t parallelize across the sequence length dimension.

For a 100-token response, the model runs 100 forward passes.

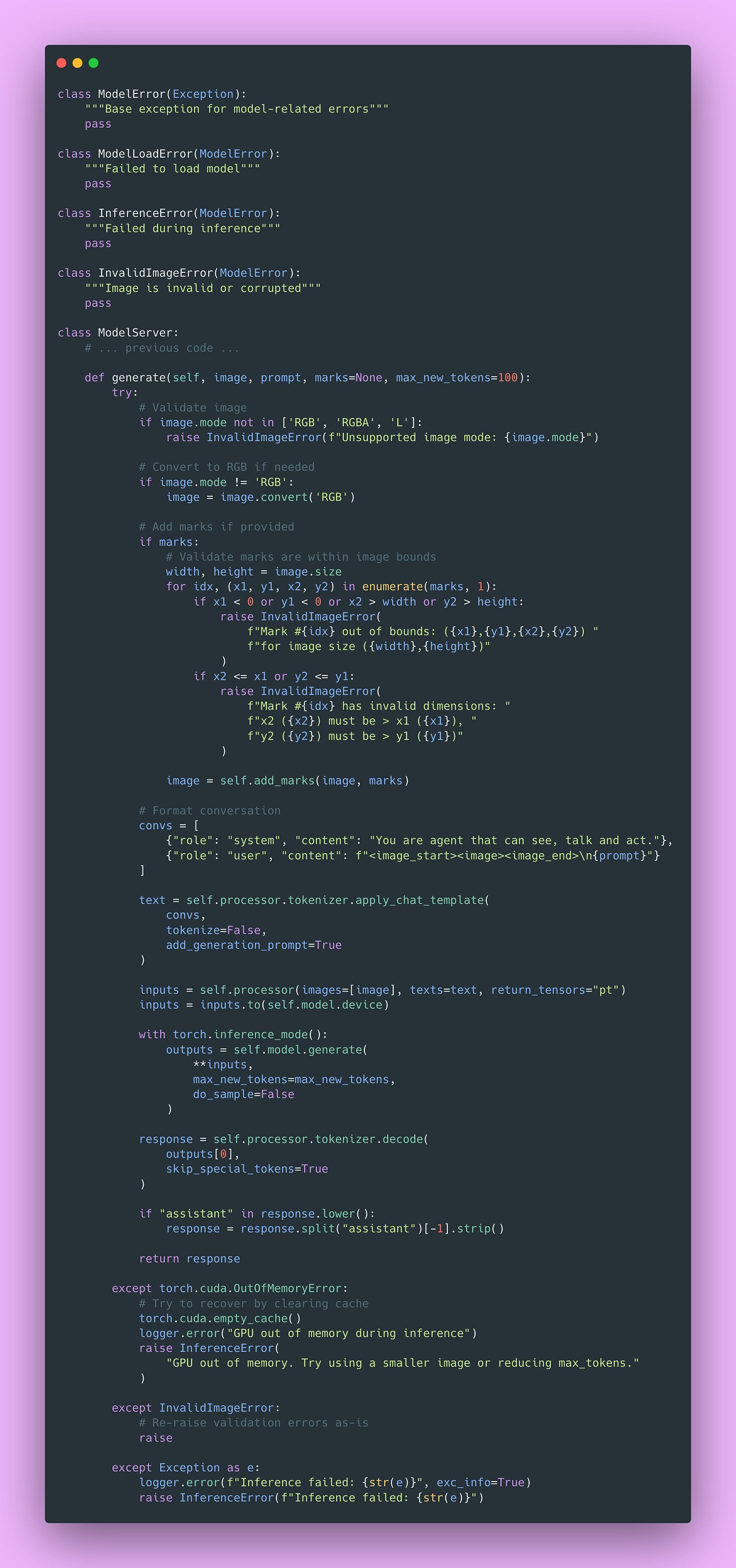

Error Handling and Resource Management

Things will go wrong. GPUs run out of memory. Images are corrupted. Networks time out. Users send invalid inputs. Let’s handle these gracefully.

Add to server/model.py:

Custom Exception Hierarchy

We define custom exceptions for different error types:

- ModelLoadError: Something went wrong loading the model (missing files, incompatible versions)

- InferenceError: Inference failed (OOM, CUDA error, unexpected exceptions)

- InvalidImageError: Input validation failed (corrupted image, invalid marks)

This lets you (and your API) distinguish between error types:

- ModelLoadError: Don’t retry, something is fundamentally wrong

- InferenceError from OOM: Retry with smaller inputs

- InvalidImageError: Client error, return 400 Bad Request

- InferenceError from other causes: Might be transient, could retry

Your API can map these to appropriate HTTP status codes. Your logs become more useful when you can filter by error type and identify patterns.

Input Validation

if x2 <= x1 or y2 <= y1:

raise InvalidImageError(”Mark has invalid dimensions”)We validate marks before attempting inference. A bounding box where x2 ≤ x1 makes no geometric sense. It would have zero or negative width. Catch this early with a clear error message.

This is way better than letting bad data propagate into the model and causing weird errors deep in the inference stack. “Mark has invalid dimensions” is much clearer than some cryptic error from PIL or PyTorch.

Memory Management After OOM

except torch.cuda.OutOfMemoryError:

torch.cuda.empty_cache()

raise InferenceError(”GPU out of memory...”)After an OOM error, we call torch.cuda.empty_cache() to release unused GPU memory. This doesn’t free memory actively in use, but it helps prevent fragmentation.

Use this sparingly because it has overhead. But after an OOM error, it’s worth trying to clean up before the next request.

What I usually do: after three OOM errors in a row, log a critical alert and exit gracefully. A process manager (like systemd or Kubernetes) restarts the service. Brief downtime beats serving incorrect results or crashing unexpectedly.

Building the API Layer

Now let’s wrap the model server in a REST API. This is the interface clients actually use.

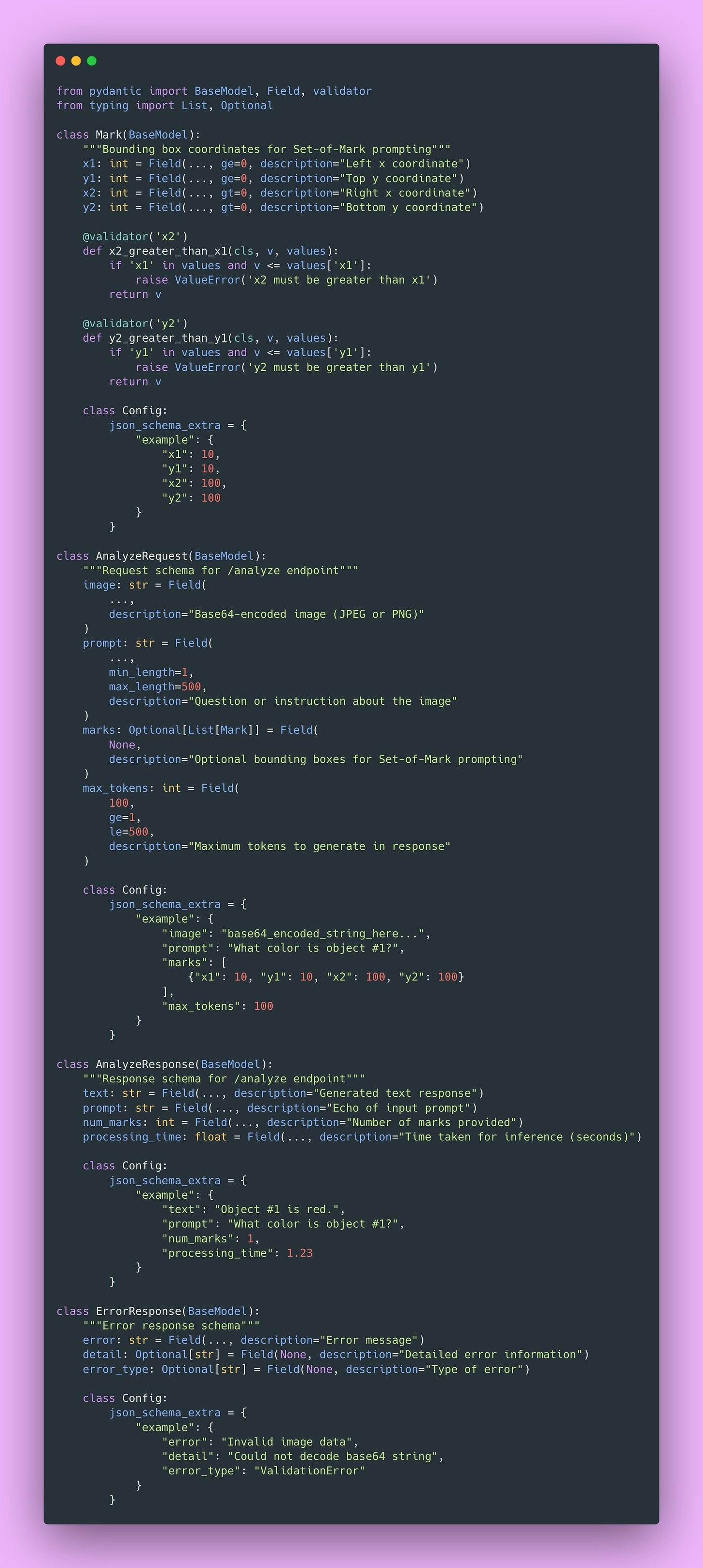

Defining Request and Response Schemas

Pydantic models define your API’s contract. They validate input, generate documentation automatically, and make your life much easier.

Create server/schemas.py:

What Pydantic Gives You

Automatic Validation: Invalid data gets rejected before hitting your code. If someone sends a string where you expect an integer, Pydantic returns a clear error message. You don’t write validation code, Pydantic handles it.

Type Safety That’s Enforced: Python’s type hints are suggestions. mypy can check them statically, but at runtime, Python doesn’t enforce them. Pydantic enforces type constraints at runtime. This catches bugs early.

Automatic Documentation: FastAPI uses these schemas to generate interactive API documentation. Your users see exactly what fields are required, what types they accept, what constraints apply, and example requests. All from your Pydantic models. Zero extra work.

Serialization: Pydantic handles conversion between Python objects and JSON automatically. You work with nice Python dataclasses, Pydantic handles the wire format.

Field Validators

@validator(’x2’)

def x2_greater_than_x1(cls, v, values):

if ‘x1’ in values and v <= values[’x1’]:

raise ValueError(’x2 must be greater than x1’)

return vValidators let you encode business logic beyond basic type checking. The @validator decorator runs custom validation after Pydantic parses the field. Here we ensure bounding boxes have positive dimensions before the request ever reaches the model layer.

This works together with the validation in ModelServer.generate(). Bad coordinates get caught at the API boundary with a user-friendly error, not deep in the inference stack.

Why Base64 for Images?

JSON doesn’t support binary data natively. Base64 encodes binary as ASCII text, making it JSON-safe. The tradeoff is about a 33% size increase (every 3 bytes becomes 4 characters), but you get simplicity and compatibility.

Alternative approaches exist:

multipart/form-data: Send images as file uploads. More efficient (no encoding overhead), but more complex to implement and test.

Binary protocols: Use Protocol Buffers or similar. Fastest option, but way more complex and less debuggable.

For most use cases, Base64 in JSON is fine. If you’re sending thousands of images per second, consider alternatives. But at that scale, you have bigger architectural concerns anyway.

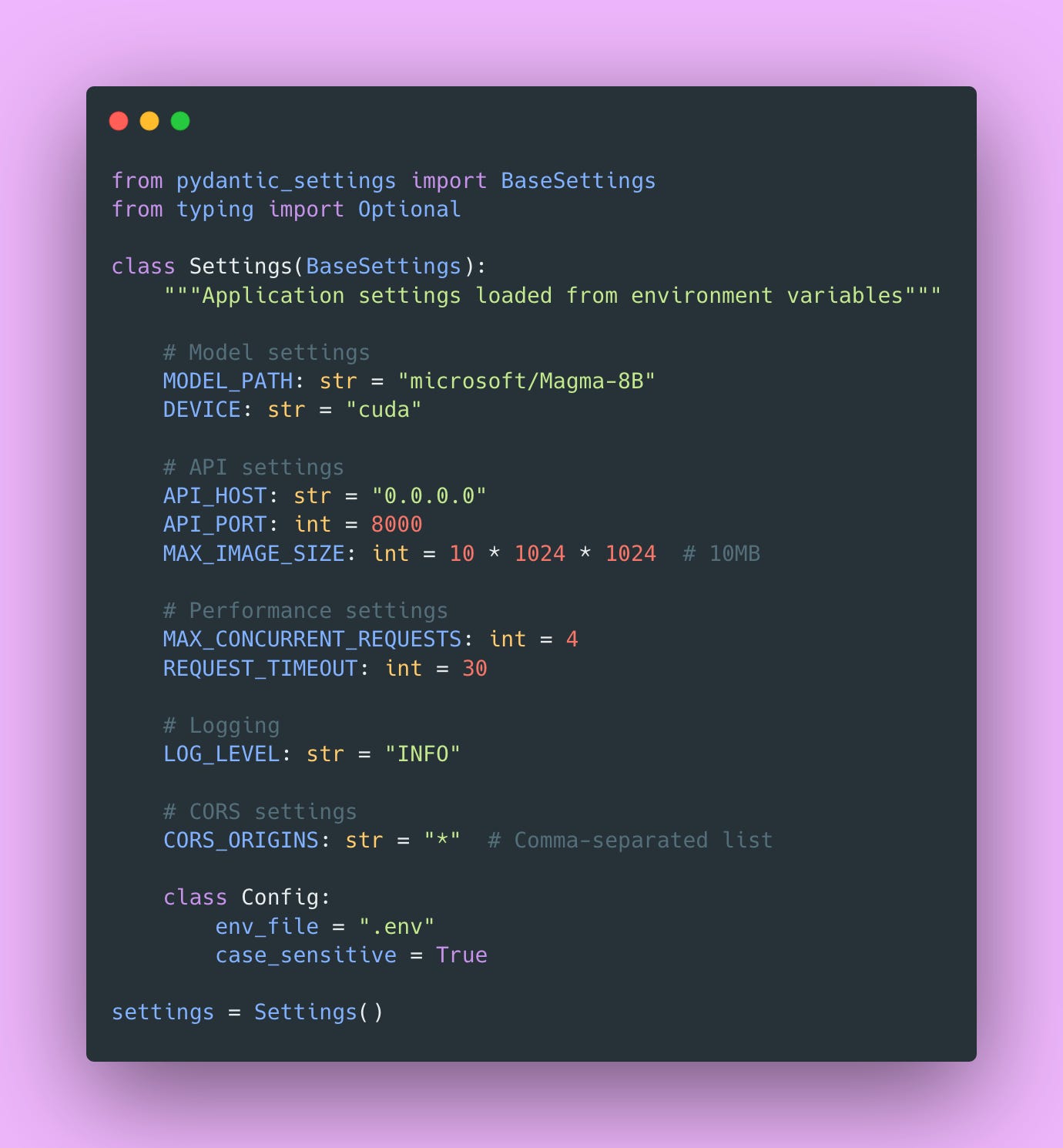

Configuration Management

Settings should live in environment variables, not hardcoded in your source. You should be able to change settings between environments without touching code.

Create server/config.py:

Why External Configuration

Different environments need different settings.

- Development: Might use CPU (no GPU), have verbose logging, and permissive CORS

- Staging: Might use GPU, have moderate logging, and restricted CORS

- Production: Uses GPU, has minimal logging, strict CORS, and monitoring enabled

You change environment variables, not code. Secrets live in environment variables or secret management systems, never in Git!

This principle comes from the Twelve-Factor App methodology: store config in the environment. It seems obvious once you know it, but violating it causes countless problems.

Creating a .env File

For local development, create .env in your project root (and add it to .gitignore):

MODEL_PATH=microsoft/Magma-8B

DEVICE=cuda

API_HOST=0.0.0.0

API_PORT=8000

MAX_IMAGE_SIZE=10485760

LOG_LEVEL=INFO

CORS_ORIGINS=*Pydantic loads this automatically. In production, you’d set these as actual environment variables through Docker, Kubernetes, or your deployment platform.

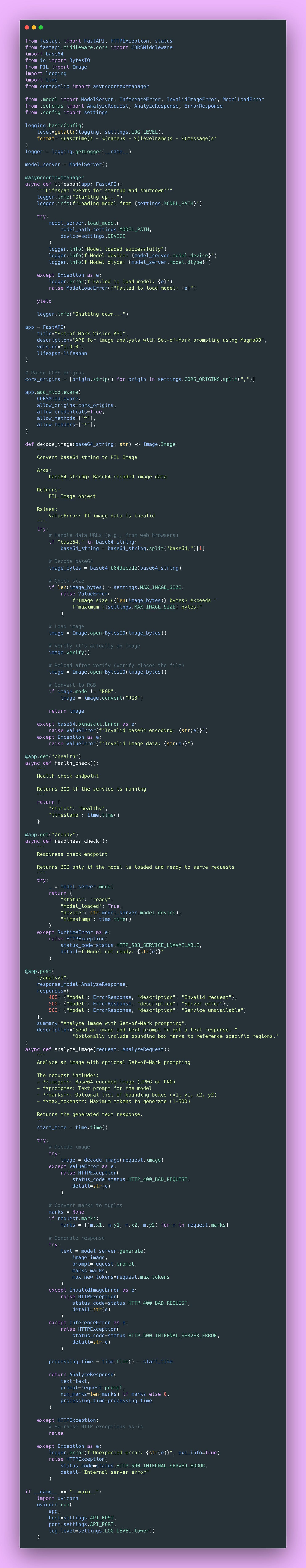

FastAPI Implementation

Now let’s build the actual API. This is where everything comes together.

Create server/main.py:

Understanding the API Components

Lifespan Events

@asynccontextmanager

async def lifespan(app: FastAPI):

logger.info(”Loading model...”)

model_server.load_model(settings.MODEL_PATH, settings.DEVICE)

yield

logger.info(”Shutting down...”)This replaced the deprecated @app.on_event(“startup”) decorator. Code before yield runs at startup, code after runs at shutdown.

This ensures:

- A model loads before accepting requests (no 500 errors from an uninitialized model)

- Resources clean up gracefully on shutdown (important for Docker containers)

- You can run initialization code that might fail (and handle failures appropriately)

Health vs Readiness Checks

@app.get(”/health”)

async def health_check():

return {”status”: “healthy”}

@app.get(”/ready”)

async def readiness_check():

_ = model_server.model # Raises if not loaded

return {”status”: “ready”, “model_loaded”: True}These serve different purposes and are essential for production deployments.

/health: Is the service running? Returns 200 if the process is alive. Load balancers use this for liveness probes.

/ready: Is the service ready to handle requests? Returns 200 only if the model is loaded. Load balancers use this for readiness probes.

Kubernetes and other orchestrators use these endpoints:

- Liveness probe: If this fails repeatedly, restart the container (it’s dead)

- Readiness probe: If this fails, stop sending traffic (it’s not ready yet)

During deployment, traffic only routes to pods that pass readiness checks. This prevents users from hitting a server that’s still loading its 16GB model, which is essential for zero-downtime deployments.

CORS Middleware

app.add_middleware(

CORSMiddleware,

allow_origins=cors_origins,

allow_credentials=True,

allow_methods=[”*”],

allow_headers=[”*”],

)This allows web browsers to call your API from different domains. Without CORS, browsers block cross-origin requests for security.

The allow_origins=[“*”] setting allows requests from any origin, which is fine for development. In production, restrict this to your actual domains:

allow_origins=[”https://myapp.com”, “https://www.myapp.com”]If you’re only doing server-to-server communication, you don’t need CORS. Browsers enforce CORS policies, servers don’t care.

Base64 Decoding with Validation

This handles several cases.

Data URLs: Browsers often send data:image/png;base64,.... We strip the prefix.

Size validation: Reject images larger than MAX_IMAGE_SIZE. Prevents memory exhaustion attacks.

Image verification: image.verify() checks if the file is actually a valid image. Catches corrupted files early.

Reload after verify: verify() closes the file handle, so we need to reload.

Color mode normalization: Convert to RGB. Some images use RGBA (transparency), L (grayscale), or other modes. The model expects consistent RGB input.

HTTP Status Codes

Different status codes communicate different things.

400 Bad Request: Client’s fault (invalid data, malformed input). Client should fix their request. Don’t retry the prior request.

500 Internal Server Error: Server’s fault (inference failed, unexpected error). Client can retry, it may or may not work.

503 Service Unavailable: Service exists but isn’t ready (model hasn’t loaded). Client should wait and retry.

This distinction matters. Well-behaved clients know:

- Don’t retry 400 errors (the problem is in the request)

- Do retry 500/503 errors with exponential backoff (it’s a temporary issue, might resolve)

HTTP status codes are a universal language. Your API speaks the same language as every other HTTP service. Use them correctly.

Building the Client

Your client’s job is simple: send images and prompts, and receive responses. Let’s build a clean Python client.

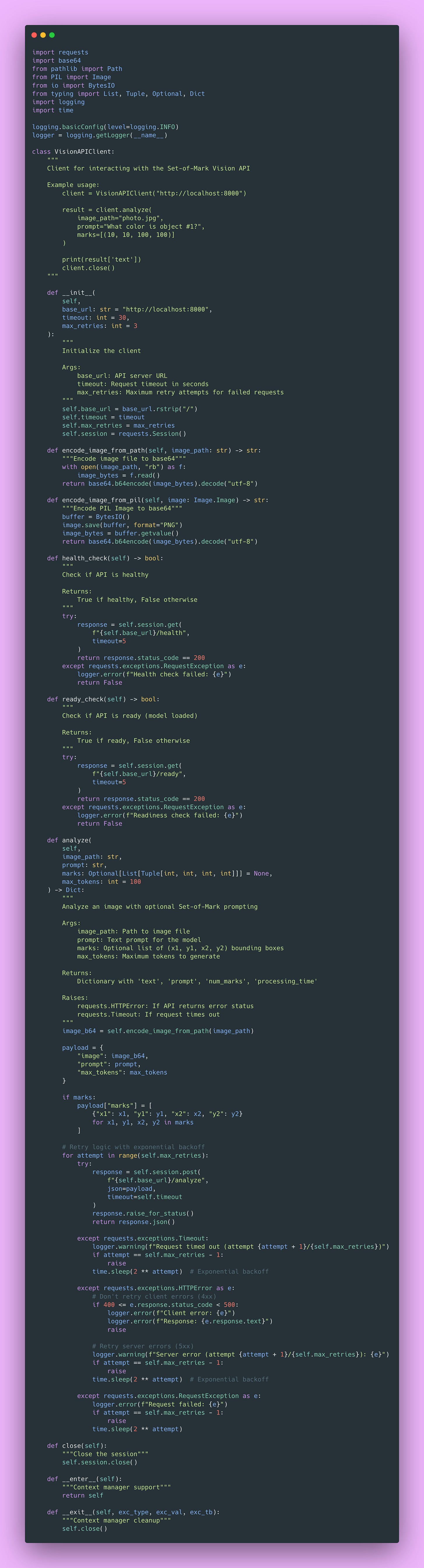

Create client/client.py:

Key Design Decisions

Session Reuse

self.session = requests.Session()TCP connections are expensive to create. A Session reuses connections through connection pooling. For multiple requests to the same host, this is significantly faster.

This is the same principle as database connection pooling. Create expensive resources once, reuse them many times.

Timeouts Are Essential

timeout=30Without a timeout, requests can hang indefinitely. Your program just waits forever, consuming resources.

30 seconds is reasonable for ML inference. Always set timeout in production. Always!

Retry Logic with Exponential Backoff

for attempt in range(self.max_retries):

try:

# ... make request ...

except requests.exceptions.Timeout:

if attempt == self.max_retries - 1:

raise

time.sleep(2 ** attempt) # 1s, 2s, 4s, ...Transient errors (like network blips or temporary server overload) often resolve if you wait and retry. Exponential backoff prevents overwhelming the server with retries.

We retry server errors (5xx) but not client errors (4xx). If you sent invalid data, retrying won’t help.

Context Manager Support

with VisionAPIClient() as client:

result = client.analyze(”image.jpg”, “What is this?”)The __enter__ and __exit__ methods let you use the client as a context manager. This ensures the session closes properly even if an exception occurs.

Testing the System

Time to see everything work together.

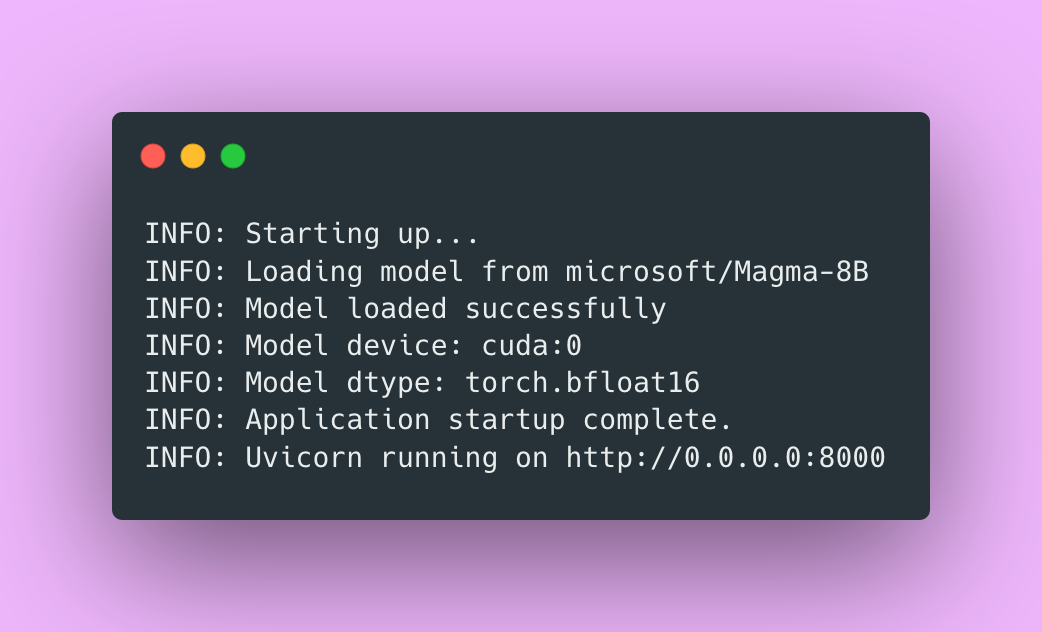

Running the Server

You should see:

First time running, the model downloads from Hugging Face. This can take a while (remember it’s 16GB). However, subsequent runs load from cache.

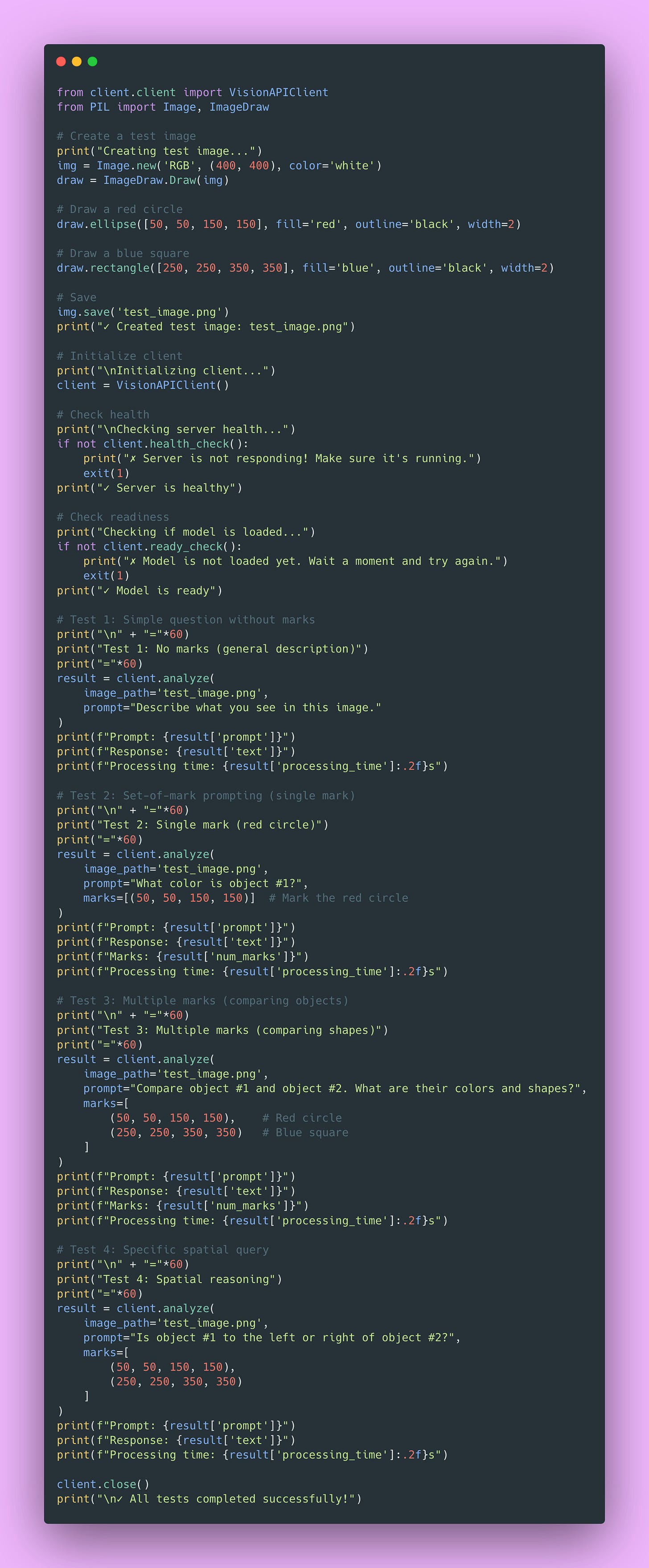

Testing with the Client

Create test_api.py:

Expected Behavior

Test 1: Model should describe both shapes (a red circle and a blue square).

Test 2: Model should focus specifically on the red circle, mentioning it’s red.

Test 3: Model should compare both marked objects, discussing colors and shapes of each.

Test 4: Model should reason about spatial relationships between the marked objects.

If you see reasonable responses to all tests, congratulations 🎉! Your Set-of-Mark vision API is working.

Common Issues and Solutions

“Model not found” Error

Check logs during startup for the actual error. Verify MODEL_PATH points to a valid model. First download can be slow. Check your Hugging Face cache at ~/.cache/huggingface/.

Try explicitly downloading the model first:

CUDA Out of Memory

You need a GPU with at least 24GB VRAM. Check with nvidia-smi.

If you don’t have enough VRAM:

- Try

DEVICE=”cpu”(it’s much slower, but works) - Close other GPU-using programs

- Reduce image size before sending

- Lower

max_tokens

Timeout Errors

First request is often slower, so you should increase timeout in client:

client = VisionAPIClient(timeout=60)Reduce max_tokens if responses are very long. Check GPU utilization during requests:

watch -n 0.5 nvidia-smiYou should see GPU usage spike during inference.

Image Encoding Errors

Verify the image file exists and is valid. Check format is supported (JPEG or PNG work, while WebP might cause issues). Try resaving the image in a different format.

Model Responses Seem Wrong

Check if model is in eval mode (we do this in load_model). Verify model actually loaded by checking the /ready endpoint. Try simpler prompts first to verify basic functionality. Save marked images and visually inspect them.

Performance Issues

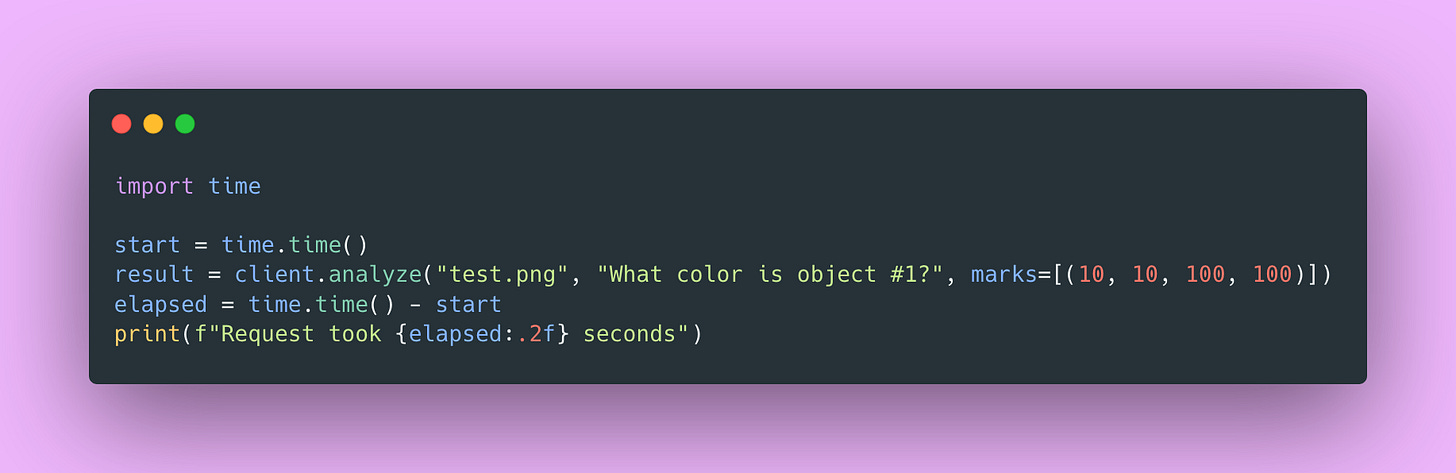

Measure request latency:

This snippet wraps a request with timing so you can see how long inference takes. First requests typically run slower because of JIT compilation and cache warming. After that, expect 0.5-2 seconds per request on GPU. If you’re seeing 10+ seconds, check that the GPU is actually being used with nvidia-smi while a request is running.

What You Built 🧰

You have a complete production-grade vision API that handles Set-of-Mark prompting.

The model server uses a Singleton pattern to load Magma8B once and serve requests efficiently. The FastAPI layer validates inputs, handles errors gracefully, and generates documentation automatically. The Python client includes retry logic and connection pooling for reliable communication.

The patterns here transfer beyond ML serving:

- Singleton pattern for expensive resource management

- Pipeline pattern for data transformation (image → marks → inference → response)

- Separation of concerns across API, model, and validation layers

- Fail-fast validation at system boundaries

- Custom exception hierarchy for meaningful error handling

- Configuration via environment variables

These show up everywhere. Database connection pools use Singleton. ETL pipelines follow the same transformation patterns. Microservices separate concerns across network boundaries. Every production system validates at boundaries and handles errors explicitly.

What separates this from a simple script or a Jupyter notebook is the infrastructure around the model. There’s proper error handling so failures don’t crash the server, health checks so load balancers know when to route traffic, logging so you can debug issues in production, and configuration management so you can change settings without redeploying code. These details compound.

Looking Ahead

In Part 2, we’ll tackle production deployment:

- Dockerization: Package everything for consistent deployment

- Scaling strategies: Handle concurrent requests, load balancing

- Monitoring: Metrics, logging, alerting that actually helps

- Performance optimization: Caching, batching, query optimization

- Security hardening: Authentication, rate limiting, input sanitization

These tools and techniques will allow you to run your application on any machine!

Try It Yourself

Before moving on, I encourage you to:

- Run the code locally and verify everything works

- Test with your own images and prompts

- Experiment with different mark configurations

- Try various prompts and see how responses change

- Measure performance with different settings

- Intentionally break something and see how error handling works

The best way to learn is by doing. Play around with the code. Change things. See what breaks. That’s how you develop intuition for what works and why.

You’re not just serving models anymore. You’re building systems.

And hey, if you made it this far, you’re doing great! Building production ML systems is hard. There’s a lot to learn. But you’re on the right path 🌟.

See you in Part 2 where we’ll make this production-ready!

Happy coding 💻